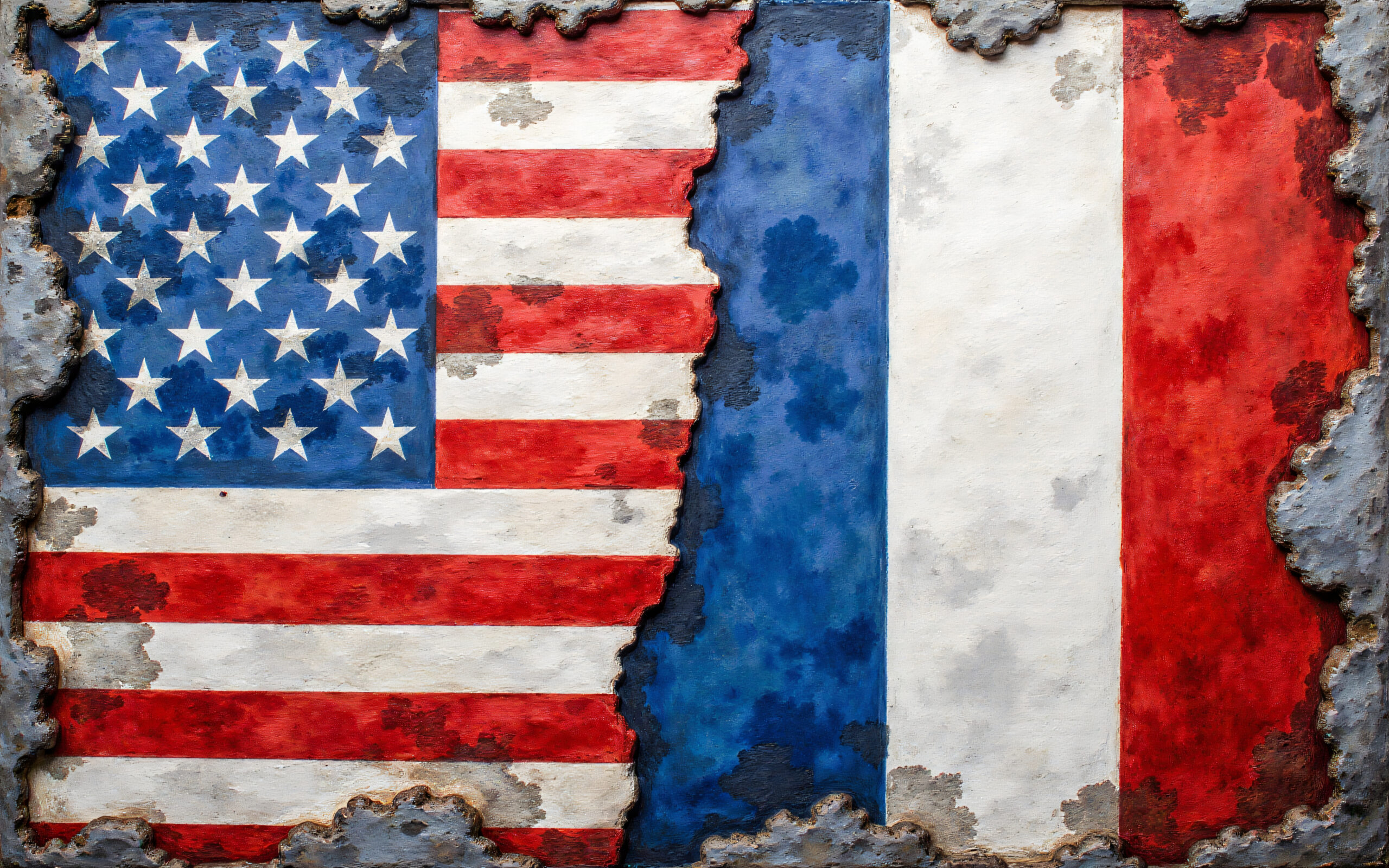

The American and French Revolutions Were VERY Different

The quest for self-government has been and continues to be a pressing issue throughout the ages—one that has often served as a call for revolution to overthrow the yoke of tyranny. These issues took center stage after the Enlightenment in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, with the rise of the Dutch commercial republic and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England.

The success of the Dutch during their golden age offered an early example of a prosperous and free state grounded in civic autonomy and mercantile freedom. England, following the revolution, became a stable constitutional monarchy, with judicial and parliamentary oversight limiting royal power and helping to protect individual rights. With a monarchy bound by the rule of law, England represented a middle ground during the Enlightenment between two radical streams that would soon burst forth.

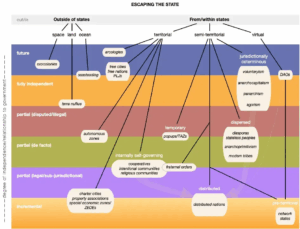

The United States—emerging from the American Revolution and rooted in the English and Scottish Enlightenment’s concern for improvement, liberty, and civil society—established a constitutional republic that rejected monarchy and hereditary privilege, instead choosing to ground its political framework in Enlightenment ideals of liberty, civic-political equality, and popular sovereignty. France, by contrast, emphasized and actuated different ideas from among the various overlapping influences of the Enlightenment that took hold in Europe. The French Revolution was based on a more abstract and dogmatic form, one that elevated idealistic reason above the more humble concerns of self-governance and resistance to tyranny. The French revolutionaries’ emphasis on rational order and universal principles encouraged the concentration of power in the hands of those claiming to represent the “general will,” leaving little room for compromise or pluralistic interpretation.

The French Revolution, inspired by these ideals, dismantled the monarchy but quickly spiraled into instability. Successive regimes—the National Assembly, the Convention, the Directory—rose and fell in rapid succession, each increasingly centralized and brutally intolerant of dissent. This pattern of rigid ideology, combined with weak institutions and inexperience, ultimately cleared the path for Napoleon’s dictatorship and the return of absolute authoritarian rule under the guise of restoring order.

The divergent outcomes between the American and French revolutions were rooted as much in institutions as they were in the respective ideological paths they chose.

French Idealistic Rationalism

The French experience illustrates the risks of idealistic revolutionary change that isn’t grounded in the institutional practice of self-governance. This trajectory wasn’t solely the result of simple immorality on the part of the leading players. There was also a structural tendency whereby arbitrary power became concentrated in the hands of people and institutions without either checks and balances or the option of meaningful dissent—for instance, the right to jury nullification.

The United States, for its part, had long-standing, well-established traditions of liberty and strong institutions, including decentralized systems of common law and jury nullification. Anglophones had already engaged in several episodes of rebellion in pursuit of greater recognition of rights, beginning with the Magna Carta (1215) and continuing through the Civil Wars (1641–1660) and the Glorious Revolution (1688). France, by contrast, lacked the historical experience and commercial base required to support a culture of rights. France’s revolution, influenced by Rousseau and centered in Paris, relied on state power to enforce liberty without the cultural and institutional foundations for a stable political order.

Before 1789, France had centralized authority with no real experience in local self-government. Power was projected downward through the crown, intendants, venal offices, parlements that guarded corporate privilege, and a Church that maintained the civil register. Taxation and justice were a patchwork. Municipal councils and provincial estates (where they existed) were narrow, revocable, and fiscally weak. The incentive structure pushed elites to court favors and rent-seek from the crown rather than build durable local power. Ordinary people interacted with the state as taxpayers, conscripts, or litigants, not as participants in budgets, policing, or schools. Politics consisted of petitions being delivered up and orders being handed down, with Paris serving as an informational and symbolic gravity well.

The French Revolution sought to completely overturn the existing social and political order, replacing it with a new, rationally constructed system imposed by the absolute power of the state. The years 1789–1794 transferred sovereignty to “the nation” but reduced countervailing players and centers of power to almost none. By abolishing intermediaries rather than building self-governing divisions of authority, the Constitution of 1791 (unicameral legislature, suspensive royal veto) made the Capital the sole prize. The incentives were thus all centrally focused: capturing the levers of power vested in the Assembly, ministries, and various clubs rather than working to enhance local governance and prosperity. War and rebellion then compressed time and further enhanced their power: under existential threat, institutions could determine and impose the fastest route to victory.

What’s your political type?

Find out right now by taking The World’s Smallest Political Quiz.

Ideology, Virtue, and Terror

Ideology reinforced these tendencies. Rousseau’s “general will,” as interpreted in revolutionary Paris, cast intermediary bodies as seeds of faction and dissent. Sieyès’s doctrine of the nation’s undivided sovereignty was used to justify a highly centralized approach: one chamber, one law, one people. Courts were retuned to a civil-law key. Judges became appliers of positive law rather than co-authors through precedent, making any resistance political rather than juridical. Even where juries existed, the deeper habit of local, low-stakes disobedience (so familiar in the Anglo world) had little time to form. Acting upon “emergencies” was cast as virtuous: enforcing liberty required sweeping away obstacles.

The Convention’s public committees—especially the Committee of Public Safety and the Committee of General Security—emerged in 1793 as extraordinary organs of governance, created to confront both foreign war and internal rebellion. Public Safety oversaw executive coordination, provisioning, and war production, while General Security directed policing, surveillance, and prosecutions. Their reach was extended through “representatives on mission,” dispatched to armies and provinces with sweeping powers to override local authorities, and through exceptional tribunals such as the Revolutionary Tribunal, which fast-tracked investigations and trials.

The centralizing decree of 14 Frimaire (December 1793) consolidated these powers by subordinating municipalities and departments to Paris. Meanwhile, a Paris-centered information market—section assemblies, the Commune, and a proliferating press—reduced coordination costs by transmitting decrees, mobilizing crowds, and disciplining provincial officials. In this low-veto, high-stakes environment, the Revolution’s institutions were less moral excess than predictable instruments of centralized control. Straying from the spirit of liberté, egalité, fraternité, the state quickly transformed into an enforcer of despotic tyranny, exemplified by the Reign of Terror (1793–1794), where an ideological commitment to reason and revolutionary values led to widespread violence and repression.

This direction was tragically evident as early as 1789, in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This document, which introduced notable advancements in civil liberties, such as equality in political representation and legal treatment (Articles 1 and 7), also imposed significant constraints upon the development of a civil society independent of the state. The Declaration established the state as the sole authority responsible for creating, interpreting, and enforcing laws. Article 3 clearly asserts that sovereignty resides fundamentally within the nation, prohibiting any group or individual from exercising authority that does not originate from the state.

Furthermore, Articles 5 and 6 specify that laws should only prohibit actions deemed harmful to society, as determined by the “general will.” They affirm that all citizens have the right to participate equally in the legislative process, with the majority representing this general will. This framework, while promoting equality and participation, ultimately centralized power and restricted the emergence of independent civil institutions (Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, 1789, Articles 1, 3, 5, 6, 7).

The revolution’s leaders believed they could engineer society through centralized authority and rational planning, which led to tyranny through the concentration of arbitrary power, as they sought to eliminate all opposition to their vision of a “rational” state. This period highlighted the dangers of enforcing abstract principles of liberty through unchecked governmental power. Ultimately, the revolution led to Napoleon Bonaparte’s rise to power and France’s descent into dictatorship, followed by a return to monarchy, which, while providing stability, sharply contradicted the initial aims of the revolution.

The American Revolution: A New Republic Rooted in Enlightenment Ideals

The foundation of American constitutionalism, in contrast to France, was significantly shaped by governance structures established during the colonial period. This aspect often remains underrepresented in discussions of American political theory. From the start, the colonists practiced—and came to cherish— local self-governance. Side by side with the influences of the Magna Carta, the unwritten norms and precedents of the English Constitution, and the writings of John Locke and other Enlightenment thinkers, the practice of self-governance laid a foundation of liberty that the colonists were loath to give up.

In Colonial Origins of the American Constitution: A Documentary History, Donald S. Lutz argues that two distinct traditions from colonial America heavily influenced the development of American constitutionalism. The first tradition involves the charters and instructions issued by the English government to the colonies, which served as a framework for governance and are partially reflected in the United States Constitution. The second is characterized by documents created by the colonists themselves, such as covenants, compacts, and ordinances, which played a crucial role in shaping the early state constitutions and the overall American approach to governance.

The colonists’ experience with both traditions led to a distinctively American practice of drafting single, amendable documents to govern political life, which they termed “constitutions.” The Pilgrim Code of Law is a prime example, drawing legal authority from both the king’s charter and the Mayflower Compact, thus demonstrating this synthesis of traditions. As a result, the American concept of a constitution evolved from these blended influences, emphasizing both the English legal heritage and the colonists’ innovations in self-governance.

From Puritans to Pluralism

In early American history, the word “constitution” didn’t have the clear meaning it does today. Many early state documents, such as the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 and the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, were referred to as “compacts” or “frames of government,” reflecting their role as agreements rather than formal constitutions. These documents combined English legal principles with innovative colonial practices, such as majority voting and popular elections.

Colonial American governance structures, while foundational to self-governance for colonists and the development of U.S. constitutionalism, were also marked by illiberal laws, such as those in some colonies that imposed strict religious orthodoxy. These laws often punished blasphemy and idolatry, even for members of other colonies, curbing freedoms through a mix of ecclesiastical and civil rule. However, such laws were gradually reformed during the eighteenth century, replacing top-down diktats with a more liberal, pluralistic approach,

However, the significant transformation in political thought emerged in the mid-eighteenth century, driven by the spread of Enlightenment ideas and the colonists’ evolving political experiences. The American Colonies underwent a profound intellectual shift that integrated Enlightenment principles with local political realities. This integration led to a new understanding of governance that emphasized individual rights, natural law, and the separation of powers, moving away from the earlier, more restrictive frameworks.

The Enlightenment’s influence on American political thought was perhaps most amplified by key texts such as John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government and Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws, which provided theoretical foundations for ideas about liberty, property, and the division of government authority. These works were widely read and discussed in the colonies, catalyzing debates about the nature of government and the rights of individuals.

Another key influence was Cato’s Letters, written by John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon in the early 1720s. This work became quite popular in colonial America, significantly shaping views on liberty by condemning tyranny and advocating for civil liberties, such as freedom of speech and a free press, and promoting the values of individual rights and opposition to authoritarianism.

Similarly, Joseph Addison’s play Cato: A Tragedy was widely admired in colonial America. It was loved especially by George Washington, who staged it for the Continental Army at Valley Forge in 1778 (despite Congress’s ban on theater at the time) for its themes of liberty, civic virtue, and resistance to oppression. Its depiction of Cato’s defiance against tyranny resonated with colonists, reinforcing ideals of personal freedom and moral courage.

By the 1770s, Enlightenment ideas and colonial self-governance practices had ignited an intellectual revolution that reshaped American political thought. This shift moved away from the illiberal, religiously driven laws of the colonial era toward individual rights, democracy, and the separation of church and state—directly influencing the ideological underpinnings of the American Revolution and the drafting of the United States Constitution.

The Declaration of Independence embodies the highest manifestation of Enlightenment ideals in the founding of the United States, emphasizing natural rights and the government’s role in protecting them. It asserts that “all men are created equal” with “unalienable Rights,” including “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” and that governments must derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The document also lists grievances against King George III for violating these principles and English common law, such as making “Judges dependent on his Will alone,” infringing on property rights by “raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands,” quartering troops without consent, and imposing taxes without representation. These represented clear violations of the colonists’ rights to property and self-governance.

Thomas Jefferson later articulated that the American founding was deeply rooted in Enlightenment ideals and the tradition of liberty. He described the Declaration of Independence as reflecting “the harmonizing sentiments of the day,” aiming to present the “common sense” of the American position in universally clear terms. In the same spirit, the Northwest Ordinance, which followed the independence of the colonies, also embodied these principles by ensuring that new territories would be admitted as equal states, not subordinate colonies—thus promoting political and civic equality and the foundations of self-governance within them. Additionally, Article 6 of the ordinance banned slavery, declaring, “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory,” demonstrating a commitment to individual liberty (Northwest Ordinance 1787). This fusion of Enlightenment ideals and self-governance therefore helped shape a unique American political identity based on liberty and democracy.

Vibhu Vikramaditya is an economist and writer on institutional dynamics, monetary theory, and business cycles. He writes at the intersection of law, economics, and liberty. You can find his other writings at the Mises Institute, and reach him at Vibhu3333@gmail.com.

What do you think?

Did you find this article persuasive?