I want to tell you a parable. Like any good parable, this one has a moral. And, like any good parable with a moral, this one ought to be retold. But when it comes to parables, sometimes it’s hard to find the original teller. Luckily, in this case, we know the author. So, in the timeless tradition of parables, I am stealing this one from Kip Hagopian. I keep the skeleton of Hagopian’s story but take a couple of creative liberties to keep things interesting.

Once upon a time, there were three sisters: Tara, Lara, and Sara Gini. They were triplets, so each was 40 years old. Having been raised in the same home, these genetic facsimiles had the same basic aptitude. And, as it happens, each sister grew up, got married, and had two kids.

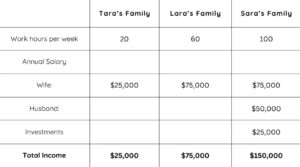

All three were nurses making $25 an hour. They each worked 50 weeks a year.

Although they were all pretty smart and had the same level of education, they differed in their work preferences—or what some might call “work ethic.”

Tara worked only 20 hours a week. She had a completely different work ethic from her sisters Lara and Sara, who each worked 60 hours per week. Neither Tara’s nor Lara’s husbands worked. Indeed, Tara’s husband was what you might call a layabout. And Tara used her free time binging Netflix or shitposting on behalf of the Democratic Socialists. Meanwhile, Sara’s husband worked 40 hours per week as a writer, making $50,000 per year (the same as his wife).

Tara and Lara spent all their income and relied on Social Security checks to maintain their lifestyles at retirement. By contrast, Sara and her husband saved much of their after-tax income over many years, eventually amassing $300,000. They put this money into an investment portfolio that produced $25,000 annually in interest and additional income.

So, the financial breakdown of each family looked like this:

Despite their different work and life priorities, the Gini families were close. They were so close that they bought homes on the same private street when a new residential development was built in their town. Their three houses were the only ones on the street and each house cost the same.

They also decided to make collective decisions democratically.

One day, the sisters agreed to pool their funds to improve the street. They were all concerned about crime and safety, and wanted a more attractive setting for their homes. So, the three families decided to install a gate at the street entrance, add lighting for additional visibility, resurface the street, and landscape the area to improve the drive up to their homes.

All the work cost $30,000. The sisters were quite happy with the outcome, and all felt $30,000 was reasonable, given the equal benefits to everyone on the street. But when it came time to divide the bill, that’s when the problems started.

Sara thought matters would be straightforward. Because the benefits to each family were the same, each sister should pay one-third—$10,000. But Tara and Lara objected.

“Why should we pay the same amount as you?” Tara and Lara asked. “You make much more money than we do.”

Sara was puzzled.

“Why is that relevant?” she asked. “Our family makes more money than yours because my husband and I work longer hours and earn extra money on our investments. Why should we be penalized for working and saving?” She added, looking at her siblings: “I’m no smarter or more talented than you. If you and your husband worked harder and saved more, you’d make as much as we do.”

“I don’t work more because I like my leisure time,” Tara replied. “I don’t save because I want to have things today. Why have things when I’m too old to enjoy them?” Tara was indignant. How could Sara — who was “rich” — ask her to pay the same amount when it was harder for her to do so?

Lara thought things over and then said,

“I’ve got an idea. Our aggregate income is $250,000, and $30,000 is 12 percent of that amount. Why don’t we each pay that percentage of our income? Under such a formula, Tara would owe $3,000, I’d owe $9,000, and Sara would owe $18,000. Since I make three times as much as Tara, I would pay three times as much. Sara, who makes twice as much as me and six times as much as Tara, would pay two times as much as me and six times as much as Tara.”

“No,” Tara said.

“No?” Lara and Sara responded in unison.

“Well, exactly,” said Sara. “What do you propose?”

Tara was ready with an answer.

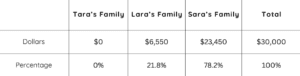

“Paying the same percentage of our incomes isn’t fair,” said Tara. “Instead, let’s do it this way: Sara, you pay $23,450; Lara, you pay $6,550; and I will pay nothing. This is the only fair division.” Lara was surprised at how completely arbitrary this proposal seemed. She was also surprised at how disproportionate it was. But because her suggested share was less than what she would have had to pay under her proposal, she didn’t object.

Sara was gobsmacked.

“You call that fair? I make only two times as much as Lara, but you want me to pay three-and-a-half times as much as she does? I make six times as much as you, but you expect me to pay almost 80 percent of the total cost while you pay zero? Don’t forget, each of us is getting the same benefits from this street improvement… Anyway, where did you get such a nutty idea?” she asked Tara.

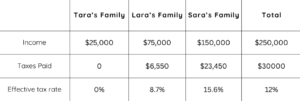

“The United States federal government,” Tara said.

She pulled out a gray booklet. “It’s all right here in the IRS tax tables. Under the current tax code, here’s what each of us paid in income taxes last year:”

“By an amazing coincidence, our total taxes paid were equal to the $30,000 we spent to improve the street. This is the progressive income tax system all US citizens live under. I don’t see why the Gini families ought to live any differently. Indeed, I think all future resource pooling should be divided in this fashion.”

“I’m in,” Lara said.

So, by a democratic vote of two to one, the cost of street improvements was divided in the following way:

And by a vote of two to one, all future improvements would be divided up the same way.

It’s a sad tale in the end because it wasn’t too long before Sara’s family sold their house and left the neighborhood.

The Moral

There are a couple of morals embedded in Hagopian’s parable, which should help to simplify and crystallize some of the issues with taxation and redistribution. Not only does it show just how arbitrary a progressive taxation system is, it demonstrates how working harder and smarter gets punished, while working less gets rewarded. It also reveals that it’s feasible for Sara’s family to leave the situation, but not the progressive tax system.

But there’s more.

While the parable does not immediately unpack the incentive effects of the progressive taxation system, we can imagine that Lara and Tara would have the incentive to vote for policies that come at the expense of Sara and her family—over and over again. In other words, it’s not just that progressive taxation and redistribution might be wrong ex ante—that is, an affront to any rights, freedoms, and proportional fairness that Sara Gini’s family might enjoy—but it might have perverse effects when we look at the system through a more consequentialist lens.

Perhaps we’ll turn to the perverse effects of redistribution another day.

Max Borders is a senior advisor to The Advocates. Read more of his work at Underthrow. This article originally appeared at FEE.