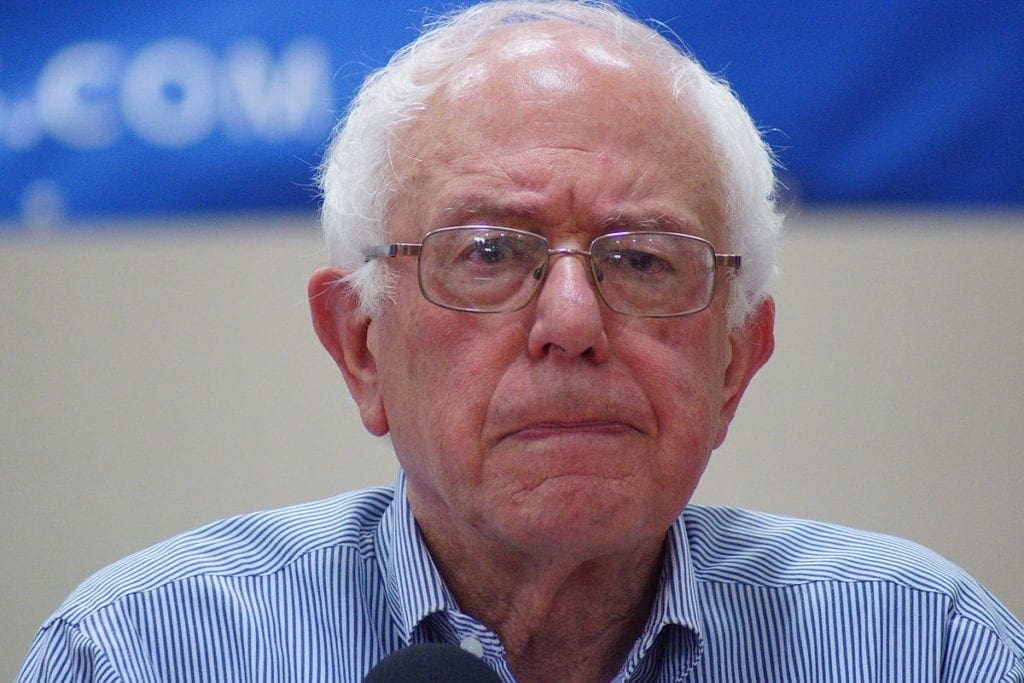

While Vermont senator Bernie Sanders might not be the de facto Democratic presidential nominee, his political philosophy continues to gain ground among the younger demographics in populous states such as California.

One of the staples of his ideology is his lack of “faith” in private charity.

Claiming that he didn’t “believe” in charities, shortly after being elected mayor of Burlington in 1981, Sanders explained during a United Way meeting that the private model of charity goes against his belief that government, and not private organizations, should be in charge of social programs.

To him, private giving is wrong because it “usurps the authority of the government,” Rev. Ben Johnson with the Acton Institute recently explained.

Despite the many decades Sanders spent as a career politician, his approach to charity hasn’t changed.

Donating only 2.2 percent of his income to charity, Sanders’ performance in the philanthropic realm is abysmal in comparison to the top Democratic presidential contender, Joe Biden, who donates about 9 percent of his money to charity yearly.

As noted by Johnson, even when Sanders gets involved in charity, it isn’t about helping people, but about propping up the state.

“In 2013, he joined his fellow Vermont legislators in briefly donating five percent of their income to charity. Sanders said he did this to ‘express solidarity’ with (generously compensated) federal workers facing budget constraints.”

To Sanders, there’s only one way to perform humanitarian work, and that is by effectively stealing the funds from the productive class.

Taxes, and only taxes, Sanders seems to contend, with both his words and his actions, can be used to perform works of charity, which must be carried out by the state in a compulsory way.

As Adolphe Blanqui, the protégé of J.B. Say, wrote in 1837, there’s a clear distinction between members of a society — they are either “people who wish to live by their own labor, and that of those who would live by the labor of others.”

Blanqui went on to explain that while the “fruit of labor is taken from the workman by taxes,” it is all done “under [the] pretence of the welfare of the state.”

The other class, therefore, “[declares] labor a royal concession, and [makes] one pay dearly for the right to devote himself to it.”

If Sanders were to look critically at his idea of how charity ought to exist only under the auspices of government, he then would have to admit that his system is only possible because there’s a parasitical group of men and women from a privileged class who rely solely on the work of others.

When so clearly laid out, wouldn’t his ideal system necessarily make him the oppressor?

As Johnson explains in his analysis, Sanders does not want the government to do charity to help those in need. If this were the case, he wouldn’t be opposed to any form of charity.

What he wants instead is to use government force to use charity as a means of bondage — complete dependence on the state is, after all, what Sanders is after. Unfortunately, a large number of others also seem to feel the same way.