What the Village of Tyneham Can Teach Us About Eminent Domain Abuse

This article was featured in our weekly newsletter, the Liberator Online. To receive it in your inbox, sign up here.

Great Britain’s compulsory purchase orders are the equivalent of America’s eminent domain laws. These powers give UK government bodies the ability to retain property even if the property owner is reluctant to give it away.

Much like eminent domain laws in America, certain UK bodies are allowed to obtain these properties by claiming that the land should be used for “public betterment.” But whether or not government is allowed to exercise this power if compensation is provided shouldn’t be the crux of the matter because value is subjective.

Much like eminent domain laws in America, certain UK bodies are allowed to obtain these properties by claiming that the land should be used for “public betterment.” But whether or not government is allowed to exercise this power if compensation is provided shouldn’t be the crux of the matter because value is subjective.

Ludwig von Mises wrote in Human Action that value “is not intrinsic, it is not in things. It is within us; it is the way in which man reacts to the conditions of his environment.” So if a man finds value in his land, even if he is being compensated for leaving against his will, the action imposed by the governmental body forcing him out is, indeed, immoral. Because value, Mises adds, “is not what a man or groups of men say.” It’s how they act that counts. Even if you agree with the government’s rationale, taking a man’s land against his will is inhumane. After all, Mises adds in The Anti-Capitalist Mentality, “there is no yardstick to measure the aesthetic worth of a poem or of a building,” so who are we to judge what is or isn’t valuable to an individual?

But history is full of anecdotes that teach us that much and yet we ignore it. Allowing generation after generation to place bureaucrats in charge of telling us what our most sacred rights truly mean.

Take the story of a village formerly known as Tiham, but which is now referred to as Tyneham.

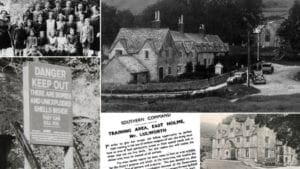

In 1943, Tyneham and the neighboring area residents were asked to leave. They were given 28 days to walk away from their homes so Allied forces could use the place as a post where they would train for the D-Day landings.

As villagers left with the belongings they could carry, villager Helen Taylor waited until the very end, posting a note on the door of the limestone church of St Mary that read “We shall return one day and thank you for treating the village kindly.”

As villagers left believing they would one day come back, government later proved them wrong. The 13th Century church endured, but folks like Taylor would never have the pleasure of holding mass there as a community again.

In 1948, the Army resorted to compulsory purchase order laws and put a hold on the village and its standing properties, claiming soldiers needed the place for military training. Up until this day, that’s what the village and its remains are used for. Now, littered with scrap and shells from decades of target shooting, only dead former members of the village are allowed to come back to be buried in the churchyard.

The image of a concerned villager asking soldiers to treat her home well may have vanished from English people’s memories, but the message remains the same. What right does a man have if not to do what he pleases with his own property? Stripping citizens from their belongings under the guise of fighting for peace may sound honorable, but in practice, all that is often left behind is garbage—and heartbreaking memories.