This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests.

The June 4, 1989 protests captivated the world’s attention as students took to the streets of Beijing to demand democratic reforms.

What looked like the first step towards China’s eventual democratization, the optimism surrounding these protests came to a crashing halt when the Chinese government responded with repression. In the ensuing weeks, the world was shocked as they witnessed a country gradually reforming its top-down economy take an authoritarian turn when the citizenry demanded more freedoms.

Because the Tiananmen Square incident is complex, we must go back in history to see what led to the culmination of this event and what it has meant for China in the present.

China’s Radical Communist Experiment

China’s 20th century was tumultuous, to say the least. In 1949, the Communists had fully consolidated their hold over China’s mainland and opposition forces were forced to retreat to the island of Taiwan. With full control of the levers of the Chinese state, Mao Zedong had tremendous ambitions of turning the once bullied country into a world power.

To take China to the next level, Mao initiated the Great Leap Forward, in which the Chinese state embarked on an attempt to transform industry and agriculture in the country through central planning. Like other central planning schemes, the Great Leap Forward failed due to its abandonment of private property and a rational price system. This failure went beyond economic performance; lives were lost in the millions. An estimated 20 million to 75 million people died during the famine caused by the Great Leap Forward, marking yet another case of democide.

Although Mao’s image took a hit after the Great Leap Forward’s failure, he channeled his authoritarian power during the Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976 in an effort to purge Chinese society of any lingering bourgeois influences. This program also failed, as economic growth stagnated and the civil liberties of millions of people were violated in the process.

From Communism to Economic Pragmatism

Mao’s death in 1976 created a power vacuum of sorts. His ambitious programs were acknowledged as failures, thus discrediting his close associates in the eyes of Communist Party leadership. The Chinese Communist Party was in need of a new strategy to move the country forward.

When Deng Xiaoping became the de facto leader of China in 1979, he understood Maoist policies had greatly impeded China’s economic growth. Channeling economic pragmatism, Deng began to liberalize the Chinese economy. Several market reforms such as land privatization and the creation of special economic zones helped China’s economy get off the ground. While limited in nature, China’s reforms did have a profound impact from the outset. China’s yearly GDP growth rate hovered around 9.5 to 11.5 percent from 1978 to 2013. During this period, millions were able to able to break free from extreme poverty.

An economic miracle was brewing in China, as experts around the world marveled at the country’s superpower potential. However, economic growth does not necessarily operate in a vacuum. As traditionally authoritarian societies like China grow economically, the citizenry, especially the newly empowered middle classes, will clamor for more political freedoms. Milton Friedman famously argued that economic freedom is a precondition for political freedom. At first glance, this dynamic looked to be the path that China was headed towards in the 21st century.

However, on the fateful month of June 1989, all hopes of democratization in China would come to a crashing halt.

The Calls for Western Democracy Intensify in the 1980s

The 1980s were a transformational era for Chinese politics. With a more stable economic footing, the Chinese middle class demanded Western-style democratic reforms such as democracy, government transparency, and free speech. These calls were not met on deaf ears. One of the more reform-minded Communist Party leaders, Hu Yaobang, the General Secretary of the Communist Party from 1980 to 1987, began floating the idea of introducing democratic reforms in China.

However, his calls for political liberalization irked the “Eight Elders” of the Communist Party, who despite their willingness to pragmatically reform the Chinese economy, was not ready for political reforms. As a result, Hu was forced to step down from his position as General Secretary in 1987, effectively becoming a political recluse afterward. His death on April 15, 1989, had a ripple effect across the country.

Student protestors demanded that the Chinese government restore Hu’s legacy once he was buried. They used Hu’s death to channel their frustrations with political corruption, employment opportunities, inflation, and the lack of political freedoms. These protests started to gravitate towards Beijing in Tiananmen Square, a site of great significance in Chinese politics during the 20th century. The May Fourth Movement of 1919 and the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949, took place in this public square. History was also made on June 4, 1989, but in this case, it ended in tragedy.

Chinese Leadership Saw Democratic Reforms as an Imminent Threat

As the protests in Tiananmen Square erupted in April, Communist party leadership grew weary of the political threat these demonstrations presented. The Chinese State Council declared martial law on May 20 and sent roughly 300,000 troops to Beijing. Once military forces reached Beijing on June 4, they fired on the demonstrators. Estimates put the casualties of the Tiananmen crackdown ranging from hundreds to thousands of deaths.

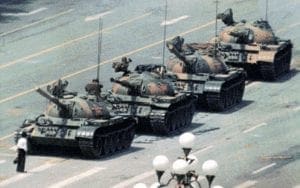

The day after the repression, on June 5, 1989, gave birth to one of the most riveting images of the 20th century. A man, famously known as “Tank Man” or the “Unknown Rebel,” blocked the path of a convoy of tanks leaving Tiananmen Square. For several minutes, the man had a peaceful standoff with the tanks, which ultimately ended in him being pulled away by two men dressed in blue. The man’s fate has still not been determined and rumors say that he was executed shortly after. Some speculate that he may have fled the Chinese mainland.

China’s Authoritarianism Lives On

Tiananmen Square was a turning point in Chinese history. After its partial liberalization of the economy during the 1980s, the Chinese state firmly re-asserted its authoritarian grip when pressure for democratic reforms arose.

Three decades later, free speech is still muzzled in China. Under Xi Jinping’s rule, the Chinese state has partnered with politically-connected tech companies to implement one of the most comprehensive censorship programs in human history. Even with sensible economic reforms, the Chinese state’s grip over society remains strong.

In contrast to the West, which reached impressive heights thanks to radical decentralization, the Chinese tale is one of centralization and authoritarian rule. Its famous dynastic cycle has witnessed Chinese empires rise and fall for more than three thousand years, with centralization being a fixture of Chinese dynasties at their peak and socio-political disintegration at their nadir. The 20th century saw it take small steps in breaking this cycle, as Taiwan separated itself from the Chinese mainland and took a market-friendly path which brought it both prosperity and enhanced political freedoms. Although a long-shot, the movement for Tibetan independence also offers a way out of China’s centralized status quo. In times when separatism is gradually becoming normalized in certain parts of the world such as Europe, it makes sense for this trend to go global, especially in regions that have never really tasted the benefits of competing jurisdictions like China.

Decentralization in China could be an actual leap forward for the country.