The End Of Prohibition Started With The States

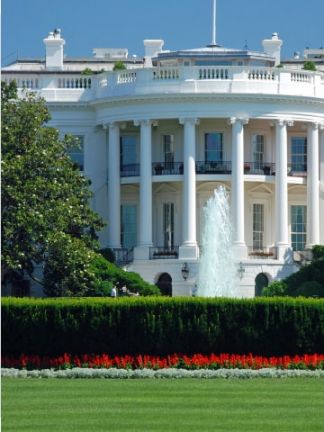

This week marks the anniversary of the repeal of prohibition of alcohol all across the United States.

The move was made official when the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was repealed by the 21st Amendment on December 5, 1933. But long before this policy shift was finally embraced by the federal government, local and state governments had already not only stood to federal prohibition in theory but also embraced policies that rendered the federal government’s decision to prevent Americans from drinking alcohol useless locally.

According to the Tenth Amendment Center, the decision to defy the federal government “created the atmosphere where this repeal was inevitable.”

Long before wealthy industrialist John D. Rockefeller Jr., a former supporter of prohibition, came to realize that laws against drinking alcohol actually led to an increase in alcohol consumption, the state of Maryland had been the only state to forego passing laws that enforced prohibition locally. Due to the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, states felt compelled to pass their own laws enforcing prohibition, but Maryland was never onboard.

Eventually, other states joined. New York was the first, passing legislation in 1923, but others quickly followed suit, feeling that the enforcement of prohibition required too many resources.

Talking about the federal prohibition, Maryland Senator William Cabell Bruce told Congress in the mid-1920s that while the amendment had been into effect for six years, “it can be truly said that, except to a highly qualified extent, it has never gone into practical effect at all.”

By 1925, six other states had passed their own laws, keeping local police from investigating prohibition-related infractions. And with cities growing tired of the feds meddling with their affairs, local officials were also refusing to provide aid. By 1928, 28 states had said no to aiding the feds in going after locals breaking prohibition rules.With both individuals regularly breaking the federal law, producing alcohol in their own homes or visiting speakeasies where alcohol consumption was the norm, and state and local officials defying the feds, Congress had nothing else to do except to move toward bringing an end to the prohibition on paper, even though it had technically been dead for years in practice.

Much like what states are doing now with the drug war, nullifying marijuana prohibition locally first, the pressure built up until it was impossible for the feds to ignore that their influence wasn’t making a dent.

Americans now understand that the fight for freedom begins locally. As libertarians, we know that this creates real competition between small, local governments, giving residents more options. With more and more states joining the nullification bandwagon, everything from federal health to monetary policies are being defied locally. And hopefully, this is just the beginning of a broader movement that might eventually completely tie the hands of the federal government, allowing individual Americans to take their lives back from regulators.

“All you do is you come here when you need money,” he told the operative.

Rechnitz had been slapped with a series of violations due to the city’s change of policy regarding subletting rooms and whole apartments at the popular lodging app Airbnb.

While Rechnitz had paid the fines, he was still looking for a way to talk to the Housing Department directly to explain why the violations were unfair. And while he had contacted de Blasio’s office to make the meeting happen in the past, he had been ignored.

He also wanted to fast track the process to sell a home that belonged to his friend, and the city was allegedly not helping.

But as soon as he refused to give the mayor any money, things began to change. As a result, Rechnitz made the contribution requested of him. De Blasio even called him in person to thank him and to let him know that the contribution meant a great deal.

In no time, Rechnitz had reportedly gotten a meeting with the city to discuss the Airbnb issue. He also got the answers he needed on the property deal he was trying to make, all thanks to the money he “invested” and the subsequent bribes he allegedly carried out so that friends would invest millions in union pension funds.

Still, the mayor’s spokesperson has denied Rechnitz’s accusations. But regardless of what officials say, we know for a fact that when someone like Rechnitz says he “owns” a politician, it might as well be true.

Men of means who are willing to do anything to bring down competition will do all in their power to have a good relationship with elected officials. Not because that’s in their nature, but because government’s very involvement in businesses through regulation allows for companies and individual businessmen with the cash to pay to keep competitors at bay by influencing policy.

And it’s thanks to this reality that governments will often pass laws implementing policies that often benefit big, powerful companies while hurting small competitors who are still trying to enter the market. That’s how large companies become bigger and stronger, while competitors have a harder time even getting started.

Who loses in the end? The consumer.

“All you do is you come here when you need money,” he told the operative.

Rechnitz had been slapped with a series of violations due to the city’s change of policy regarding subletting rooms and whole apartments at the popular lodging app Airbnb.

While Rechnitz had paid the fines, he was still looking for a way to talk to the Housing Department directly to explain why the violations were unfair. And while he had contacted de Blasio’s office to make the meeting happen in the past, he had been ignored.

He also wanted to fast track the process to sell a home that belonged to his friend, and the city was allegedly not helping.

But as soon as he refused to give the mayor any money, things began to change. As a result, Rechnitz made the contribution requested of him. De Blasio even called him in person to thank him and to let him know that the contribution meant a great deal.

In no time, Rechnitz had reportedly gotten a meeting with the city to discuss the Airbnb issue. He also got the answers he needed on the property deal he was trying to make, all thanks to the money he “invested” and the subsequent bribes he allegedly carried out so that friends would invest millions in union pension funds.

Still, the mayor’s spokesperson has denied Rechnitz’s accusations. But regardless of what officials say, we know for a fact that when someone like Rechnitz says he “owns” a politician, it might as well be true.

Men of means who are willing to do anything to bring down competition will do all in their power to have a good relationship with elected officials. Not because that’s in their nature, but because government’s very involvement in businesses through regulation allows for companies and individual businessmen with the cash to pay to keep competitors at bay by influencing policy.

And it’s thanks to this reality that governments will often pass laws implementing policies that often benefit big, powerful companies while hurting small competitors who are still trying to enter the market. That’s how large companies become bigger and stronger, while competitors have a harder time even getting started.

Who loses in the end? The consumer.