I am going to make a bet with you. I bet (some undisclosed large sum of money) that you do not wake up each morning, look in the mirror, and say, “How can I do evil today?”

Sure, some people do bad things in pursuit of personal or ideological objectives, or in the heat of the moment. But very few set out to do bad things for the sake of doing bad things. Most of us would prefer to make the world a better place…or at least not actively make it worse.

At this point, we have all seen those clickbait titles that start with “One Weird Trick…” and then go on to offer some quick-fix cure or “life hack.” Obviously, I am not going to use such a title here, but the truth is, I could have.

Because there really is one simple, easy technique to avoid making the world a worse place.

The Signature Bad Thing

As we have established in our previous installments (1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5), Consentism is

The moral philosophy, grounded in the facts of nature, that the valid consent of the individual is the only rightful foundation for any exchange, agreement, authority, or encroachment upon the person, property, or liberty of another.

As such, the signature bad thing—the bad thing at the root of all bad things—is to do things to people to which they did not consent.

There’s your one weird trick, right there. Just don’t intrude upon the person, property, or liberty of others without their valid consent.

This leaves us with a big problem, however. Actually, about 200 big problems:

GOVERNMENTS.

If the consent of the individual human person is the fundamental unit of moral concern—and it is—then every form of involuntary governance is morally impermissible. And every recognized government on the planet falls into this category.

Democracy does not solve the problem.

There is no valid claim anywhere in the universe that can justify violations of consent. Most people understand this when it comes to tradition, the divine right of kings, and other historical claims. But the same applies to democracy.

Voting—either directly or for representatives—does not solve the consent problem. Whether you vote or not, whether you win the vote or not, things will be done to you to which you did not consent—even when you have not harmed anyone else. Voting ≠ consent.

The same applies to the imposition of the system as a whole. For consent to be valid, it must be voluntary, explicit, transparent, informed, and revocable. No government on the planet receives valid consent. None. Zero. Nada. Not even the United States, not even in 1789, when it was brand new. Forced consent ≠ consent.

The bottom line: involuntary governance is categorically illegitimate. It cannot be justified by notions of majority rule, democratic participation, or even benevolent outcomes. You lost the vote…It’s for your own good…You benefit anyway…You consented by staying—none of these can be used as moral defenses. Nothing justifies imposing governance on unwilling individuals, just as nothing justifies any other nonconsensual incursions upon the person, property, or liberty of another. They are both manifestations of the same impermissible act.

We know better now.

Systemic violation of consent is inconsistent with the overall philosophy that Enlightenment-era thinkers (and later, the American Founders) were expounding. These brilliant philosophers and statesmen were products of their times, however, and could only draw upon what they knew. As such, the zeitgeist in the 17th and 18th centuries was that monarchy should be replaced with democracy.

Democracies (yes, even constitutional republics) ought to have been a temporary stop on a journey toward truly consensual arrangements, but at the time, no one had yet thought through how to accomplish such arrangements at the societal level. The concept of “implied” consent to the “social contract” was thus a kind of philosophical cheat code, to get around the fact that they couldn’t think of anything better.

In the two centuries since, we have made significant progress, with the help of some truly brilliant thinkers. From the inescapable logic of Lysander Spooner to Paul Émile de Puydt’s concept of panarchy…from Hayek and Mises through Rothbard to David Friedman, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Robert Murphy, and many others, we now have a clear picture: social order can be achieved without violations of individual consent.

We are, of course, a long way from being able to put this knowledge into practice at scale. And we would not want to see governments collapse without something better to replace them, for as history has shown, such collapses tend to lead not to greater freedom, but to chaos followed by new oppressions.

Yet the first seedlings of a new, polycentric model for human organization are being planted even as we speak. As such, now is the time to start thinking about how to help that process along and ensure that the world of the future is as peaceful, just, and consensual as we can make it.

It may seem like putting the cart before the horse, but it really isn’t. We need to start envisioning this stuff now, so it is ready when it is needed most.

What’s your political type?

Find out right now by taking The World’s Smallest Political Quiz.

Tensions

So what would the world look like if individual consent were truly respected? There are some strange tensions in this question, and they lead to answers that might surprise you.

We know for sure that no one may rightly be subjected to any exchange, obligation, or exercise of power without his or her valid consent. So how do we solve that equation?

Simple! We abolish all violations of individual consent and create rights-respecting societies. No more involuntary governance. Classical liberalism for everyone! Problem solved.

Except…not so fast.

What if someone wants to live in an absolute monarchy? What if someone wants to live on an Amish farm? What if, for that matter, someone wants to continue living under the kind of governmental systems we have now?

If we prevent them from doing so, aren’t we violating their consent every bit as much as if they force us to live a certain way? People ought to be free to consent to things that you or I might not wish to consent to. I mean, right? Isn’t that what consent is all about?

Protective action is only justified in response to real trespasses against person, property, or liberty. I may rightly use force if you attempt to assault me, steal from me, or enslave me. I may not do so to compel you to live a certain way, or to make you live under a particular kind of government…even if we all voted on it!

So how do we resolve this tension? How can we arrange things so that no one is subjected to violations of consent, and different people can choose different ways of life, and yet still maintain a beneficial social order?

It’s complicated, and this piece will be one of several in which we work through the problem to find an answer.

One size fits all?

One major impediment to solving this problem is something we can call the fallacy of the single-solution system. In simplest terms…

There is a pervasive assumption that the only way that humans can coexist is for everyone within a given area to live under a single system. This view is so pervasive and deeply held that people will blithely assert—as if it is a KnownFact™—that it is entirely justified to use any amount of force to compel everyone to live under one system.

What do you mean, you don’t want to be a part of this system? Everyone is a part of this system. No one gets to live any other way. It simply isn’t done. Now sit down and shut up…or else.

There have been times and places where this was done with religion. It was expected that everyone in a given population would adhere to a particular religion, and those who did not were shunned, attacked, or exiled.

Here in the West, we have since figured out that this is entirely unnecessary. Religious persecution is also evil, of course, but let us focus on the fact that it simply isn’t necessary for everyone to be of the same religion. American streets are lined with many different churches (often side by side, especially in small towns), and their parishioners live side by side in perfectly pleasant neighborhoods. Society hasn’t crumbled as a result.

Why is it presumed that this cannot work for governance?

Governments claim to rule every person and piece of land in a given area. Why is that claim presumed legitimate?

Why are the geographical borders of states sacrosanct? Do you notice how it is deemed entirely reasonable for states to grow in size, but it is beyond the pale to suggest that they should ever shrink, or that a country should be divided? There is no logical justification for this. There is no reason why the boundaries of a state must be of one size rather than another…or why they must continue only to expand, until the inevitable war with a neighboring state erupts.

And there is no reason why everyone within a given set of boundaries must live a particular way.

Yet try telling that to the average citizen and watch what happens. You will find that the fallacy of the single-solution system runs deep. We have our work cut out for us.

Polycentrism

Fortunately, that work has been aided by a lot of brilliant thought over the last 200 years.

In his 1860 essay “Panarchie,” Paul Émile de Puydt offers a plausible vision of how people can choose from among competing providers of governance services without changing their geographic location. In the years since, numerous others have provided detailed descriptions of how consensual and private systems have worked in the past, how they are working in limited ways today, and how they can work at scale in the future. The blueprint is there.

So what does this knowledge get us? Simply put, it gives us a way out.

If people were no longer forced to surrender their freedom and submit to the nonconsensual rule of a government, what would happen?

One thing is for sure—people would find a way to create order. No one likes chaos.

People would do so in one of four main ways:

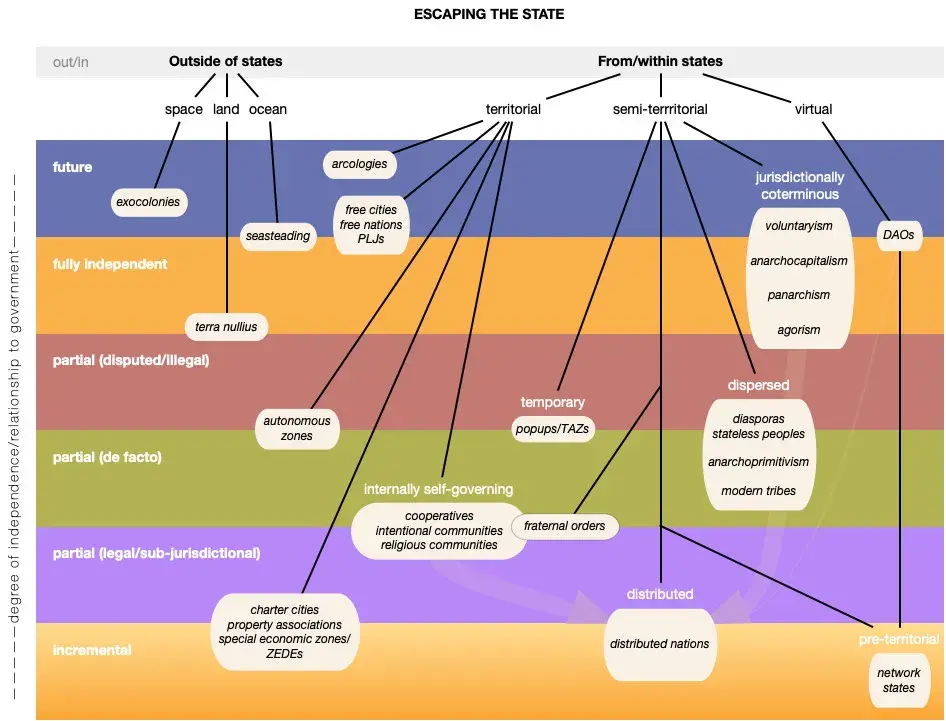

Non-territorial, semi-territorial, and virtual

Market anarchism (anarchocapitalism)

In a truly free and open market, agencies would arise to provide desirable services—security, justice, infrastructure, etc.—to willing customers. Indeed, those agencies already exist today: private security and arbitration are big business. In the absence of governments forcibly imposing a monopoly of authority, such agencies would compete to provide these services on a much larger scale, at better prices, and far more efficiently.

Panarchy

In de Puydt’s original vision, people could remain right where they are and simply choose from among any number of jurisdictionally coterminous governance providers. This is similar to market anarchism, but people would be citizens of competing governments rather than customers of competing agencies. (Note that most of the work on market anarchism has been done after de Puydt’s death.) I suspect the market-anarchic version will end up being more popular, but de Puydt’s version is a viable option in a truly consensual social order.

Distributed phylarchy

In such a condition, we would also see groups of people cohere in “phyles” (a term popularized by Neal Stephenson, from the Greek word for “tribe”) based on shared identity or common interests. Some such groups would form territorially exclusive polities (discussed below), but they might also cohere in local enclaves, or as distributed individuals, without relocating to a single geographical location. DAOs, fraternal orders, religious communities, network states, distributed nations, and diasporas might all increase in organization to the point where they begin to provide governance or governance-like services.

(Note: there is significant overlap in the Venn diagrams of all the above possibilities.)

Territorially exclusive

Private polities

In a condition in which consent is respected, some individuals and associations would establish polities on private property, based on mutual interests, identities, or objectives. These would start small, but some would eventually reach the size of city-states and beyond. They would also range in character, from free cities to for-profit micronations to intentional communities and everything in between.

Jurisdictional Ecology

And this brings us right back to the beginning.

As believers in the principles of consentism and voluntary cooperation, we will have to accept that some polities and associations will form that we would not want to be a part of. Consentism does not, and must not, prescribe one particular type of social arrangement. Rather, if we are to be consistent, we must insist only that people be free to choose their own social arrangements.

As a result, we must support the emergence of a polycentric jurisdictional ecology, in which any sort of arrangements might arise. Our only demand can be that no one is forced to participate in any particular arrangement. This must apply equally to traditional governments (from which we must be free to secede) and any new polities or associations that may someday form (in which we must not be required to participate).

As we will discuss in the next installment, this new ecology will require the acknowledgement and respect of certain rights: to ESTABLISH, AFFILIATE, and EXIT from polities; to SECEDE from involuntary governance; and to REMAIN on one’s unincorporated property, free from any compulsion to associate with any polity or government.

Ultimately, the goal will be a condition of consensual order, in which individuals, agencies, and polities can maintain peaceful relations without the serial violations of consent that characterize the governments of today. To this end, we will also propose wording for a common respect protocol—a simple framework agreement to help maintain this condition.

Here too, we must not impose anything—such a protocol must be entirely voluntary. We must find a way to convince, not coerce. To woo with words rather than demand and dictate. Consensual order will be an emergent pattern, not a world government.

This is not sci-fi. This is the direction things are heading. It will take some time, but the first stones are already being laid in pathways to this future.

Our task now is to figure out how to get there as quickly as we can, and how to stay there once we’ve arrived.

Questions? Input? Concerns? Feel free to email me at chriscook@theadvocates.org

Christopher Cook is a writer, author, and passionate advocate for the freedom of the individual. He is an editor-at-large for Advocates for Self-Government, and his work can be found at christophercook.substack.com.

What do you think?

Did you find this article persuasive?