My wife and I just returned home from a long-weekend getaway to San Antonio. We wanted a brief escape from the cold of our northern home and a fun place to celebrate our twenty-second anniversary. San Antonio is perfect for both.

The Riverwalk was everything my wife told me it would be. (She had traveled there for work a few years ago.) Set below street level along a winding, narrow stream, it feels like its own world. In the morning, it’s for lovers and families: quiet and serene. At night, it’s party central.

We also found our way to the bustling and colorful Mercado, where we met some lovely people and wheeled and dealed for a few souvenirs. Then we grabbed lunch at Mi Tierra, where the food is comforting, the decor is unruly, and the air crackles with life.

We spent most of a day at Sea World, the highlight of which was our beluga encounter. They are such curious, friendly creatures! Even before the encounter officially began, they were eagerly popping up out of the water in an effort to see us and say hello.

Our hotel was right across the street from the Alamo. This enabled us to spend time there on two separate occasions and really soak it all in. And there is a lot to soak in.

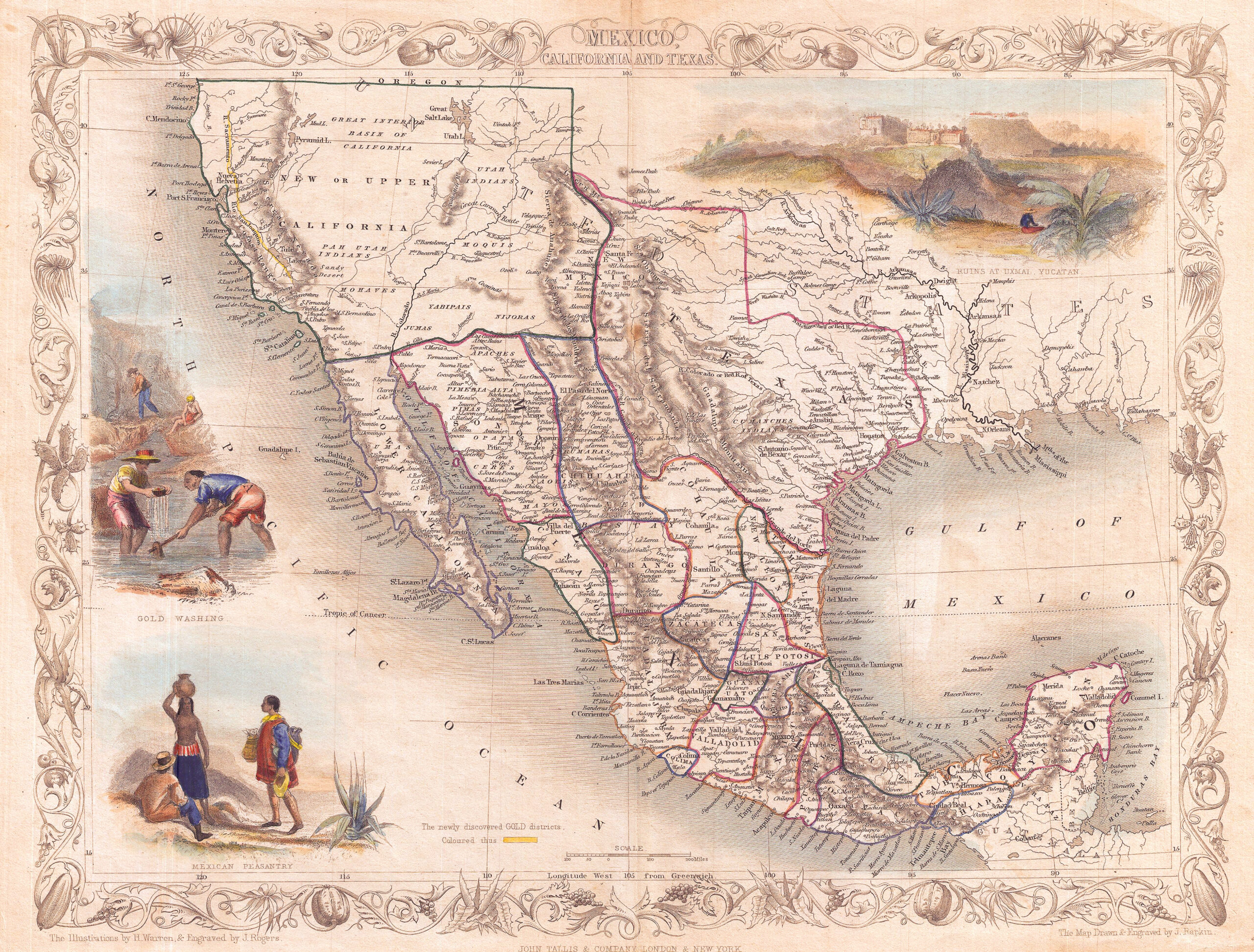

One thing that repeatedly struck me, while exploring the Alamo’s history, was just how many times “ownership” of that part of the world changed hands. First, Spain claims it (and France toys with the notion of doing the same). Next, it’s Mexico. After that, it’s the Texas Republic, and now, it’s within the borders of the United States.

But the more I considered each one of these ownership claims, the more absurd they began to appear.

Are such claims legitimate at all? Can anyone own vast areas of land simply because they say they do? Let’s find out.

Your land is your land.

Ownership of real property is an entirely legitimate outcome of an individual person’s self-ownership. A full defense of property rights will have to wait for another time. For now, in brief…

In order for the bite of food you are about to eat to be useful to you, it must be your bite of food. In order for the tools you craft to be useful, they cannot belong to everyone; they must belong to you. You need a place to shelter and a section of ground to call your own. If your land, house, bed, or stove belongs to “everyone” or “no one” or someone else besides you, then they are useless to you.

These things must be yours, and so long as you did not take them by force from a previous owner, they are yours. Full stop. They are an extension of you, and part of your rightful domain of self-ownership. No one else has any legitimate moral authority to say otherwise.

There are several ways by which you can acquire property. You can homestead unoccupied places; produce new things from existing resources; receive property in voluntary transactions with others; or receive property as a gift or bequest.

All of these are entirely legitimate. The Lockean Proviso—that one must not hoard all of something, such that there is nothing left for anyone else—is valid, but almost never actually comes into play.

What’s your political type?

Find out right now by taking The World’s Smallest Political Quiz.

All land is not your land.

Property rights are not infinite, however.

From a human perspective, Saturn’s moon Titan is unowned. However, I cannot simply claim that all of Titan is mine. If I did, no one would take the claim seriously. There are no grounds by which I can legitimately lay claim to the whole of Titan.

The reason is simple: in order to claim an unowned place, you have to be able to do something with that place. That is what we mean by homesteading. You get to claim only that which you can use or transform.

This is deep, organic knowledge—the kind that everyone knows intuitively and can only be undone by indoctrination or sophistry.

This truth operates throughout the natural world. Wolves occupy an amount of territory that they can use, and packs are pretty good about respecting each other’s territorial ranges. Bears pick a site and dig a den for their wintertime naps. They do not claim every possible site; they claim that which they have transformed into a den, and other bears generally respect the claim.

In the same way, a pioneer moving into the wilderness builds a house and fences off a section of land for a flock of sheep or a farm. Thieves might not respect his claim (violating property rights is what thieves do), but everyone else generally does, because he has claimed only what he can homestead. His homestead is an extension of his self-ownership, and it is necessary for his continuance and thriving.

But if that same pioneer were to try to claim everything from the Mississippi to the Rockies, we would all laugh in his face. And behind his back. And in the history books for centuries to come.

So why don’t we do the same when governments make the same exact claim?

A Tale of Texas

Let us use a brief history of Texas for a simple case study.

Pre-Columbian Texas

Dozens of tribes are known to have lived in the area that is now called Texas long before the arrival of European explorers or settlers. Before them, paleo-Indians hunted and gathered on the land. Recent evidence suggests that others—possibly even Neanderthals or Denisovans—may have been in the area 100,000 years ago or more.

Individual legal property titles may not have existed at the time, but territorial ranges are also a legitimate form of property. This is the area in which we live and hunt. A known territorial range is especially helpful for hunter-gatherers, since that mode of life is more zero-sum (there are only so many buffalo and berries in a given area).

Some tribes were peaceful and respected one another’s territorial ranges. However—contrary to the gauzy revisionism of today—many others were quite violent. The Comanche, for example, routinely pillaged, killed, and enslaved their neighbors, ultimately creating a territorial empire that included parts of five current U.S. states and Mexico.

Spanish Texas

The practice of laying claim to vast territorial empires (and then enforcing that claim with violence) is not exclusive to Europeans or to any single group. It is a human phenomenon, and it is dishonest revisionism to suggest otherwise. As it turns out, however, Europeans were better at it, and even more brazen in their claims.

The history of Spanish Texas began in 1519, and it went something like this: Spanish explorer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda arrived, took a look around, and said, Yep, all of this is Spain’s now.

That’s it.

They didn’t move in settlers. No one homesteaded anything. Spain simply said, You see all that land from the Rio Grande to the Red River? Yeah—that’s ours now. (And then they started raiding the area for slaves.)

In fact, they didn’t bother establishing any permanent presence until they saw the French build Fort St. Louis almost 170 years later. For all that time, the Spanish considered Texas theirs simply because they said so.

Mexican Texas

Despite this baseless claim of “ownership,” history refers to the area in question as “Spanish Texas” until 1821, when Mexico won its decade-long war of independence from Spain. At that point, it becomes Mexican Texas.

Mexico’s Federalist Constitution of 1824 was quite reasonable, as such things go, and that, along with promises of land grants, induced large numbers of Americans to renounce their U.S. citizenship and agree to become part of Mexico.

These land grants—as all such grants in the New World—involved land that had once been part of native territorial ranges. Though land displacement is not a uniquely European crime, this was certainly one more unfortunate consequence of the clash of civilizations in the New World, and of the fact that land is a scarce resource.

However, at least the land was granted to actual humans who were going to do actual things with it: ranching, farming, commerce, and all the other business of living. This act of homesteading gets us closer to legitimate property ownership than the simple claim by a nation-state that “All this is ours.”

The Republic of Texas

Despite that improvement, a fundamental problem remained: the state (in this case, Mexico) still acts as a superior landlord—the ultimate owner of all properties within its claimed boundaries. Despite not living on the land or doing anything useful with it, government officials claim the authority to tax your property, control what you do with it, and take it from you when they see fit.

In a very real way, the state is still claiming “All of this is ours.”

In Texas, the problem of government interference in private lives, property, and finances deepened dramatically when Antonio López de Santa Anna abrogated the Federalist Constitution of 1824 and established a centralized military government. This betrayal angered Texians (and many Tejanos), prompting the Texas Revolution.

The rest is history: The citizens of Gonzales refusing to surrender a cannon to the Mexican army. The dogged defense of the Alamo. The massacre at Goliad, and the ultimate victory of the Texans at San Jacinto.

But as Texas passed into the control of the Texas Republic, and ultimately became a part of the United States, the fundamental problem has never gone away. The United States still says, Your land is actually OUR land.

Indeed, this is a worldwide phenomenon. States claim to be the superior landlord of just about all the land on the planet.

But on what grounds?

Your land is not their land.

Property is necessary for all living things—from a butterfly’s patch of sunlight in a forest to a bear’s den to the house in which you sleep and cook your meals. Animals have quite sensibly developed non-lethal methods for establishing property rights, just as we have quite sensibly developed legal titles and peaceful transfers of ownership.

All of this is conducive to continuance and to a general condition of stability and harmony. And all of it can be justified by the needs of self-owning beings, and by the fact that no one has any natural rightful claim to say otherwise.

The absence of any such claim is, indeed, the salient fact here. You can search the universe from end to end, and you will never find any natural moral justification for one being to exert authority over another. If such authority is not granted through valid consent, it must be imposed by force. (And consent is only valid when it is voluntary, explicit, transparent, informed, and revocable, which means that voting does not constitute real consent.)

Government officials claim to be the ultimate owner of your land. You know you didn’t consent to that. They know you didn’t consent. That is why they will arrest you and confiscate your home if you do not pay your property taxes.

All they have is force.

You can justify individual ownership based on the fact that you need property to live, and that you acquired your property in voluntary exchanges—without theft or violence.

The state has no such justification. All they have is the sword, and the absurd claim that everything from river to river or sea to sea somehow belongs to them.

In a very real sense, nothing has changed since Alonso Álvarez de Pineda looked at a quarter million miles of wild land and said Yep, all of this is Spain’s now.

PS: A reminder for children of the 1980s—the Alamo has no basement.

Questions? Input? Concerns? Feel free to email me at chriscook@theadvocates.org

Christopher Cook is a writer, author, and passionate advocate for the freedom of the individual. He is an editor-at-large for Advocates for Self-Government, and his work can be found at christophercook.substack.com.

What do you think?

Did you find this article persuasive?