Last year, I left my native Germany in search of greater freedom in Paraguay. The following is taken from an interview with a Venezuelan who did the same. In part 1, we spoke about his journey from his native land to the Netherlands. Here, we continue the discussion and learn why he—like so many others—finally decided that Europe was not the free land he had hoped.

“But like the 50 or whatever is a little much,” Fernando recalls of the tax situation in the Netherlands. The OECD puts the Netherlands’ “tax wedge”—the share of labor costs taken in taxes—at 35 percent, roughly five percentage points higher than in the United States. But payroll taxes are only the start. Stack that with VAT, excise duties on fuel and energy, and housing-related levies, and the bite adds up quickly.

“I saw my money going away for somebody else—who was not me. The government.” There he was: a Venezuelan who had dropped out of school at eleven and moved to the Netherlands at twenty, now increasingly disillusioned with the European model of the state.

In 1993, against all odds, Fernando Guerra had escaped before the total downfall of his homeland. Now he felt a different version of the same squeeze. The dream of freedom in Europe, he says, was fading. He felt trapped again.

Immigration Working as Intended

Stories like Fernando’s complicate Europe’s loud immigration crisis. He is precisely the kind of newcomer who contributes and should be welcomed.

These days, more and more Europeans criticize immigration. They point to some immigrants who do not integrate and instead live off state subsidies. But that complaint ignores the more basic mechanism: governments created the subsidy structure in the first place, and predictable incentives do the rest. If you build a system that pays people not to produce, you should not be surprised when some take the offer. Immigration is not the problem; many immigrants are good people fleeing bad circumstances. A big welfare state is the problem.

Fernando is a useful counterexample. When he arrived in Amsterdam, he did not receive any handouts. His decision to flee Venezuela for the Netherlands forced him to learn Dutch and English from scratch, on the street. He did just that, staying true to his motto: “If you want something, you make it happen.”

The only language I knew was Spanish. Nothing else… English was easy for me. I don’t know why, but I picked it up fast—because I liked it. And then I knew I needed to speak the other language, Dutch. I started immediately, that same year. It took me about a year, maybe a year and a half.

Take a second to internalize that. This young adult who escaped a collapsing country arrives on another continent without any money. He knows no one and doesn’t speak the local language. Yet he does not try to find his countryfolk and stick only with them. Instead, he takes action to learn the language and integrate right away—and all of this more than a decade before smartphones were invented. With the right attitude, barriers to freedom can be overcome.

Self-Reliance

In the 1990s, squatting in long-vacant properties was often tolerated in the Netherlands and not prosecuted as a crime. The bed–table–chair rule of thumb said you had to bring in these items fast to show that you used the place as a dwelling. This made the difference between occupants being treated as trespassers versus requiring a formal legal process to be kicked out.

“We started to live for free on squat… Empty houses, empty places,” Fernando recalls of that penniless time. It was a common practice for activists and drifters. Unauthorized electricity hookup was the norm.

That time was a crazy time, but it was a good time. That was my first two years. It was incredible. I learned a lot. And then after two years, I was getting enough money playing on the street to [sublet a home informally].

He found it grotesque that some in his circle relied on government support. “I never thought to ask the government to help us, never,” he says. While busking and laboring at a local market, he built up contacts and eventually started working as a tour guide.

In 2001, he went back to Venezuela to file paperwork for a Dutch residency permit. He worked hard, and in 2004, Fernando bought an apartment. After years of living in gray areas, he had become a regular citizen. He survived on voluntary exchange and started “contributing to society.”

What’s your political type?

Find out right now by taking The World’s Smallest Political Quiz.

A Heavy Tax Burden

The price of being a “legitimate” resident began to weigh heavily on him, however. The bills started coming: income tax, social security contributions, fees for permits…

I started to learn a lot of stuff. Paying taxes … for the house, taxes for the water, that was something new for us … taxes for the car, oh my god, taxes for [this and] that. So at the end, I was getting my bills, my money was disappearing. So, I was not saving money.

By 2007, he was ready for the next step in his entrepreneurial career. Since leaving school at eleven, he had worked as a shoe shiner, busker, tattoo artist, street musician, and market vendor. In 2007, he opened his own goldsmith business.

It went well: “And then I started to make good money,… but once again I was paying a lot of taxes.” He spent years grinding. He became a father. But in his soul, unease was growing. Signs of shrinking freedom—all too familiar from his early life in Venezuela—began to appear.

Another Exit

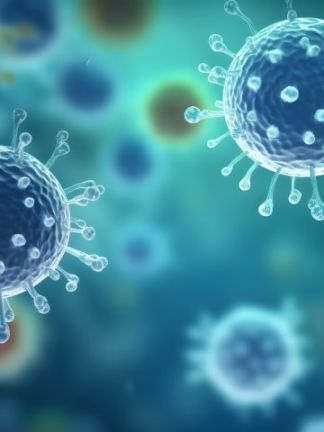

2020 was the tipping point. Curfews and heavy state interference in daily life were not new for Fernando. “Europe is going downhill too. Europe is [like] the beginning of Venezuela in the ’90s … A lot of demonstrations are going to come; a lot of manipulation.” The lockdowns opened Fernando’s eyes to just how much things had changed.

When you are really busy doing a lot of stuff, you don’t look at the weather. You don’t care about the weather. You just make money and live your life … You see it when you are not allowed to go out. You see, what’s going on with the weather …. It’s raining already for twenty days.

The decision to leave was not difficult this time. The parallels were glaring. “During COVID, I had a really difficult time … because I was not allowed to go on the street and I was already thinking about Venezuela, how everything started.”

Boarding a plane is difficult, however, if none are taking off. Unable to leave immediately, Fernando took the time to do proper research and prepare his exit.

It was smoother than the first one. Fernando knew what he was looking for and what he had to consider. He also had the means to do a proper investigation. Between 2020 and 2023, he spent long stretches of time in Portugal as a semi-escape.

“I went to the government in Holland in November 2024. I said ‘Listen, I’m leaving the country. I need paperwork saying that I’m leaving tomorrow.” He boarded a plane to Florida, spent a few months there, and finally left for Paraguay. Once again, he voted with his feet.

Another Plan B

Unlike when he moved to the Netherlands at twenty, Fernando arrived in Paraguay relaxed. Experience and diligent research helped. “I know the language, I know the culture a little bit.” Asked to describe the country with one word, he chooses “opportunity.”

Although he considered handling the immigration process himself, he chose to work with Plan B Paraguay, a Paraguay-based firm specializing in residency and relocation services. “I could do it, but it would take longer. And I already knew that time is money.” He also values the circle he’s found, a circle of expats and locals trading practical tips about daily life and ways to grow, reinforcing the self-reliance he’s always leaned on.

Life in Paraguay is simple. Infrastructure is not as polished as in the West. From time to time, it rains so hard that you risk damaging your car’s engine if you drive, since there’s so much water on the streets (no exaggeration). But Fernando likes the breathing room: regulations are few, neighbors mind their own business, and the government hardly bothers him. As long as you do not harass the people around you, no one cares.

Fernando says he has reclaimed his personal sovereignty and tries to live as a responsible, moral individual. He supports those around him. Just after our interview, he left to help an American family by translating in the hospital.

Fernando’s contact with those he left behind in Venezuela is respectful but infrequent. A huge portion of the Venezuelan population has left. Those who stayed either couldn’t leave or support the regime, Fernando tells me.

He could have stayed in Venezuela and, later, in Holland—grumbling about taxes and rules, resigning himself to quiet frustration. Instead, he drew a line in the sand and chose the way out. He chose exit.

For people who do not want to cross the globe but still want to keep their sanity, he offers this tip for keeping stress down: “Don’t look at television; don’t go to the cinema; don’t listen to radio. Just enjoy the real stuff, real meat, real food, real experience.”

Liberty, he insists, is a lifelong pursuit. You have to actively maintain your freedom. “Freedom is in your hands. You take it or you don’t take it.” He rejects the urge to “save” the world and brings it back to responsibility for one’s own life: “I don’t want to save everyone. I just want to save myself and my family and the ones around me. That’s it. I take my freedom seriously.”

If you want to contact Fernando, feel free to reach out to him via Instagram.

See The Burden of Freedom for the backstory.

With a background in business and tech, David brings clarity to ideas of individual freedom and Austrian Economics. He left Europe in search of liberty and he authors the Substack publication "In Pursuit of Liberty."

What do you think?

Did you find this article persuasive?