Stop Being Disappointed in Politicians

There’s an awful lot of disappointment among those who thought the Trump administration was going to shrink the government. Among the sources of that disappointment is Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill,” which will increase the Federal deficit by $3 trillion.

Conservative defenders of the bill argue that short-term compromises are necessary to secure long-term gains. These defenders will have to forgive us for our skepticism—especially those of us who are old enough to still be waiting for the government shrinkage promised by President Reagan in the 1980s.

It is also notable that while the OBBB does include some entitlement cuts, it increases military spending (David Stockman does a great job of explaining why that’s not only unnecessary but the opposite of what is needed) and spending on border control.

So if this talk of “short-term trade-offs for long-term gains” sounds like a lot of nonsense to you, you’re not wrong. However, there is a logic to this nonsense, and it’s worth understanding.

What we are witnessing in D.C. serves as a kind of object lesson: Even a conservative dream candidate, or dream team, cannot really make a dent in government growth and spending. Contrary to what most pundits will tell you, this is not due to flaws in those candidates but to the nature of the political machine itself. To grasp why requires an understanding of this machine and how drastically it differs from the way most of us have been raised to think about it.

Government officials are not held accountable for their actions

The first thing to understand about the machinery of the state is that it—or rather, those who act on its behalf—are not held accountable for its actions in the way that ordinary citizens are.

When a legislator writes a law that violates the constitutional rights of his or her constituents, the worst that will happen to that legislator is that he or she may fail to be re-elected. When a governor enacts policies that violate the rights of people living in his or her state, and even cause physical harm and destruction of property belonging to those people, the worst that will happen, beyond possibly not being re-elected, is that that governor may face a lawsuit and be told by a court to stop doing these things. There will be no financial penalties (or, if there are, they will be paid by taxpayers, not the criminal governor), and importantly, no jail time.

This is critical to appreciate. This simple fact means that government officials are free to act in ways that no one else is. They are shielded from liability for the consequences of their actions in ways that no one else is.

What’s your political type?

Find out right now by taking The World’s Smallest Political Quiz.

Government is the REAL monopoly

Americans are taught in school about the evils of monopoly. They are taught that we need government to protect us from monopolies that arise in free markets. This is both historically and economically incorrect, but it’s what most of us are taught to believe. Yet somehow, very few of us ever question the biggest monopolist in our lives: The government itself.

Here’s what the textbooks tell us about monopolists: Once they gain control of a market, they are free to raise prices and/or reduce the quality of the good or service they produce, because they are no longer threatened by the possibility of competition.

Of course, in a real market, dominant players are never guaranteed their position of dominance. Competitors might appear out of nowhere at any time and become a threat—which is why, in actual free markets (or even free-ish markets), big, powerful companies generally don’t behave the way the textbooks tell us they will.

But you know who does behave this way?

That’s right. It’s the government.

Politicians’ incentive is money, not freedom

Americans are told that their politicians “represent” them. However, this belief quickly falls apart under just a little scrutiny:

To begin with, what does it mean to “represent” a large, diverse population of people with varying, and sometimes conflicting, wants, needs, values, and priorities? If the answer is that the politician represents the interests of the majority of these people, even that is not true.

Generally speaking, politicians do not win elections based on the extent to which they appeal to their constituents, but on the extent to which they are able to raise money to run an effective campaign. This need to raise money puts their interests squarely with those of the individuals and organizations supplying this money.

So what does this mean? What do people generally want from the politicians to whom they give money? It is possible that they might want more freedom, fewer interventions into their lives, lower taxes, and less government spending. But is there much of a political market for these things?

No, there’s not. And here’s why:

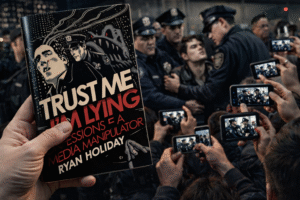

Think about what politicians have to “sell” to their supporters. What do they have to offer? Promises to vote for more liberty and less government spending? Sure. But where’s the money in that? It’s not that there is no one willing to spend their own money supporting small-government candidates, but that’s not where the real money is. The real money is in the direct, tangible benefits politicians can offer to their supporters. Namely: Intervention into markets on their behalf.

This can come in the form of regulations that make it harder for others to compete with the donor entity, or in the form of more direct largesse: government contracts and subsidies.

And remember, those cronies—the ones getting the largesse—are also the ones receiving newly created money before it has penetrated into the rest of the marketplace. (Inflation doesn’t just make you poorer; it makes them richer.) This is the history of the regulatory state, and it is the economics of crony capitalism.

This is what principled, small-government political candidates are up against. It’s a slush train that feeds itself and keeps getting more wealthy and powerful at everyone else’s expense. How do you think it’s going to work out for a political candidate who proposes to derail that train? Not only is their position unpopular with all the folks riding on the train, but there is simply not much money in advocating for their position. Going up against this self-perpetuating slush machine is a losing proposition.

Understanding how the political machine operates is essential if we are going to solve the problems it has created.

Government officials are not held accountable for spending deficits. Any honest business would shut down if it couldn’t balance its books. But not the state. Given this, legislative debates and hand-wringing over budget deficits are nothing but theater. (And not very entertaining theater either.) Add to this that politicians have powerful incentives to keep spending on the particular interests that support them and their positions, and we have a one-way slush train to economic collapse.

Once we understand the incentives, it ceases to be a mystery when a Republican-dominated Congress fails to demand real cuts in spending and makes excuses for supporting massive growth in government debt.

The bigger lesson, though, is this: We do not vote our way out of this mess. Certainly not at the Federal level.

So what do we do?

There’s a lot we can do outside of the realm of national electoral politics. Nullification is a tool that can be used in a variety of circumstances to divorce state and local communities from Federal control. Building parallel systems and communities is also essential.

But even if none of these solutions turn out to be the right ones, it is important that we recognize one thing: That the “solution” we’ve been promised as the way to exercise our “self-governance” is no solution at all. It is not an effective tool for preventing government from intruding into our lives and consuming our wealth. And it is hardly self-governance in any reasonable understanding of that concept.

Recognizing this is absolutely critical if we are to attain either of these goals. The first step towards finding solutions that work is acknowledging the ones that don’t.

Bretigne Shaffer is a former journalist who now writes fiction and commentary and hosts a podcast. She blogs at Bretigne, and her fiction writing can be found at Fantastical Contraption.

What do you think?

Did you find this article persuasive?