How many political ideologies have there been over the last 150 years?

In all likelihood, a series of familiar words has begun flashing through your head. Communism. Fascism. Socialism. Conservatism. Libertarianism.

Perhaps you drilled down a little further: Democratic socialism. Progressivism (America) and social democracy (Europe). Paleo-conservative, social conservative, fiscal conservative.

Maybe you can describe some of the differences between Italian fascism and German Nazism, or between Marxism-Leninism and Maoism.

Maybe you can list every single flavor of the libertarian rainbow, from most to least austere: Anarchist, minarchist, Objectivist, Public Choice School, Austrian (Misesian), Austrian (Hayekian), Chicago School…

And so on.

Every one of these ideological categories can be further subdivided, and there are plenty of others I didn’t mention. But what if I told you that at one level of analysis, there aren’t dozens of ideologies, but only two?

A bigger tent

In Part 1, we discussed the tendency of political movements to fracture—often over comparatively minor differences. Discussion becomes debate. Debate becomes division. Division becomes dissolution. Political movements possess a seemingly bottomless capacity to fork into ever-smaller splinter groups. In Part 2, we explored some of the internal divisions within the freedom movement, and why libertarians are especially prone to fractiousness. Before we can discuss some specific solutions, however, we have one more task. I would like to convince you that the freedom movement is bigger than you think…and that it ought to be considered so. This is where the concept of two political ideologies comes in. Disclaimer: The exploration upon which we are about to embark will include a large amount of generalizations. These will be accurate, but they will, of necessity, ignore a variety of nuances. I acknowledge that the nuances exist and that they are important, but for the purposes of this discussion, we must focus on the generalizations. Furthermore, in our core questions section below, it will appear as if I am delivering a blanket condemnation of the political left. I do believe that the ideology of the left gets the answers to all of these questions wrong, and much to the dismay of humankind for the last 200 years. However, I also acknowledge both the many exceptions that underly these generalizations, and the heartfelt good intentions of many of those who have inclined leftward over the years.A freedom scale

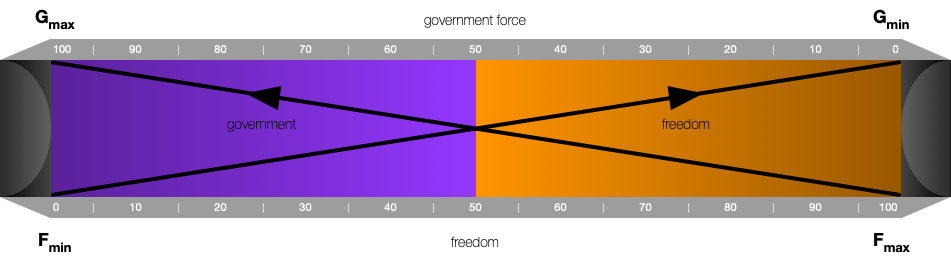

In many ways, politics can be boiled down to a single question: how much? How much freedom? How much government? In his natural state, the individual is free. Governments restrict a measure of that freedom, and the bigger a government gets, the more it restricts. The relationship between government and individual freedom is, roughly speaking, inversely proportional. Thus, we can imagine a single-axis political spectrum that measures amount of individual freedom, with the minimum to the left and maximum to the right, moving in inverse proportion to amount of government along the same axis. A “freedom scale,” if you will.

But then a question arises—can we conceive of some kind of a center point on this spectrum? And if so, what would cause a person, policy, or political faction to fall to one side or another?

Left and right

If we look at our freedom scale, we can easily recognize that ideologies that prefer a larger, more active government would range to the left side (more government, less freedom), and the ideologies that want to limit the size of government would range to the right (less government, more freedom). Conveniently, this largely matches the ideologies of left and right as we understand them today. For ease of discussion, then, we will call these the (modern liberal) left and (classical liberal) right: from progressivism and social democracy all the way leftward through national socialism, state socialism, and totalitarianism to the left, and from conservatism through libertarianism, minarchism, and ultimately anarchism to the right.The core questions

We have a good start here. But can we get even more specific? Is there something that definitively places an ideology in the purple section to the left or the orange to the right? While we must acknowledge that this is an inexact science, the answer is yes. Upon examination, we find that these two ideologies, writ large, are on opposite sides of a series of ideological objectives and premises. We will call these the distributive objective, distributive premise, unit of moral concern, delivery vehicle, power principle, and limiting principle. The left’s distributive objective is to equalize outcomes: to engineer a chosen pattern of material distribution. The right’s distributive objective is to protect equal opportunity: to allow material distribution to unfold organically, through the voluntary exchanges of a free market. In order to justify their distributive objective… The left proceeds from the distributive premise that the collective has a claim upon the property of the individual. The right begins with the distributive premise that your property ought to belong to you. These premises follow from each side’s unit of moral concern: For the left, the fundamental unit of moral concern is the group. For the right, the fundamental unit of moral concern is the individual. For the left, all of the above requires a tremendous amount of force… Engineering a chosen pattern of material distribution requires centralized control over an economy. People don’t like having their stuff taken from them, so any claim by the collective upon the property of the individual must be forcibly imposed by some small group claiming to speak for the collective. And the same goes for any actions that require the individual to subordinate to the utilitarian aims of the collective. As a result, the left’s objectives require a delivery mechanism with a lot of power—the kind of power that can only be wielded by a large and assertive state. The right, by contrast, needs far less force, or none at all… Free markets are, by definition, uncontrolled. They are an emergent phenomenon in which prices, wages, and resource allocation reach an ever-changing equilibrium through the voluntary actions of millions of individuals acting in their own interests. Conservatives, libertarians, and anarchists may differ on whether any interventions whatsoever are needed, but none wants to increase the amount of central planning. Similarly, respecting the property and rights of individuals requires far less force than does taking their property and treating them as sub-units of a collective. Here too, conservative, libertarians, and anarchists differ, but only by degree. Conservatives have largely accepted the Enlightenment-era argument that some small amount of government will better protect rights than none at all. Non-anarchist libertarians dial down the amount of government they deem acceptable. Anarchists hold that since any government is an initiation of force against, and violation of the consent of, the individual, none is morally permissible…but that order can be achieved in other ways. As such, taken in total, the right’s delivery mechanism is a moderately limited government (conservatives), a more limited government (libertarians), or no government at all (anarchists). The delivery mechanisms of left and right are fundamentally in opposition, and ultimately come from, and engender, two very different views of power: The left’s power premise—from the modern liberals of the West to the authoritarian socialism of the 20th century—is that power is a desirable good, to be used to achieve the aims of those who wield it. The classical-liberal right’s power premise is that power is, at best, a necessary evil. As a result… The left has no limiting principle on the size of government—no internal rule that says, “We should stop here.” This is why whenever the left’s external opposition relents or is overborne, the country in question moves toward totalitarianism.* They have no principle to tell them not to. After all, if power can be used to do “good things,” then the more the merrier, right? The right, by contrast, does have a limiting principle, a wording for which we might approximate thusly: The correct amount of government is that which maximizes enjoyment of individual rights while minimizing disruptions thereto. We will call this amount the “sweet spot.” A conservative—again, clinging to classical liberalism as it stood in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—will tend to hold that because the “state of nature” is insecure, it is better to surrender some property and rights to a limited government on the expectation that that government will protect and secure the rest. A (non-anarchist) libertarian will tend to the same view. However, the libertarian is more austere in the amount of government deemed acceptable, and will especially reject the prosecution of (non-defensive) wars, enforcement of laws against victimless “crimes,” or redistribution of wealth for any purpose. As stated above, an anarchist will argue that A) our shared principles, taken to their logical conclusion, deem unprovoked initiations of force and violations of consent to be morally impermissible, B) all involuntary governance, however limited, initiates force and violates consent without provocation (through taxation, ex ante laws, and the imposed “social contract”), and is thus morally impermissible, and C) it is possible to produce order without the use of involuntary governance, and therefore D) the sweet-spot amount of government is ZERO.Bottom-lining it

The left, writ large, presumes government and then allows for some amount of freedom. The right presumes freedom and then allows for some amount of government. In either case, amount of government (in inverse proportion to amount of freedom) is the unit of measure. There are obviously different flavors, styles, and factions. Yet at this level of analysis, we may say that there are just two ideologies—each with a volume knob. Turn conservatism down a few notches (reduce the acceptable amount of government) and you get the more moderate flavors of libertarianism. Keep going and you move through more austere forms until finally, when you click the knob off entirely, you get the anarcho-libertarian preference for zero (involuntary) governance. And we can run this same exercise on the left side of the scale. This sort of analysis raises questions, calls for further elaboration, and shines a bright light on that which divides us. As such, it runs the risk of making more enemies than friends. Needless to say, that is not my goal. Quite the contrary, I would like to convince conservatives, libertarians, and anarchists that it is to our advantage to think of each other as part of the same broad movement, rather than picking at the scabs of our differences. And so… To libertarians, I know that conservatives can be frustrating. I know that some social conservatives and national security types cross the centerline on some issues. But it’s just those issues. On most others, they are well within the classical-liberal compass, and disagreement becomes primarily a matter of degree. Conservatism, as we understand it in the Anglosphere and the broader West, shares the same philosophical substrate, and much of the same ideological provenance, as libertarians. At very worst, conservatives are potential allies to (gently and slowly) convince, not enemies to constantly berate. Also, as Hayek and others have trenchantly observed, some of the social values and temperamental traits typically associated with conservatism would almost certainly be necessary for any truly libertarian community to function successfully. We may disagree about many things, but we share an overall desire for greater freedom and general skepticism toward power. we can use that as the starting point for an alliance rather than obsessing over our differences. To conservatives, I know that you tend to rely far more heavily on instinct than on principles. Indeed, some species of conservatism see this as a feature rather than a flaw. However, once you embark on a journey of discovery through the philosophical roots you share with libertarianism, you may very well find yourself becoming more libertarian. The logic is hard to refute! Even if you retain your Burkean overtones, a better understanding of first principles makes everything so much clearer. With this understanding, libertarians will cease seeming weird and scary. You may even come to realize that they are the keepers of the flame. Like high priests toiling away in an arcane library, they plumb the depths of principles all classical liberals share in common. Instinct, accumulated human wisdom, prudence, and first principles are not mutually exclusive. Quite the contrary—when integrated together, they are far more powerful than each is on its own. To my fellow anarchists (voluntaryists, ancaps, etc.), Yes, we’re right about everything—haha, just kidding. Sort of. But seriously, we are right about a heck of a lot. We are also tiny in number. How does it help us to act as though our closest allies are our direst enemies? How does it help us to treat minarchists like Maoists? How does it help us to argue doctrinaire details in a world awash in statism? Do we want to win a debate, or do we want to actually do something? There is nothing wrong with progress toward a goal. Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good!What matters most…

For all our differences, we are part of a single larger phenomenon. We all come down on the same side of each of the dichotomies listed above. We all want to be more free than we are now. We may argue about degrees and details, but we agree on the direction. That, my fellows, is where our focus should lie.*Indeed, this appears to hold true across the board, and thus we can and should state it as an axiom of politics. To wit, (Because the left has no internal limiting principle), The left will always expand governance in direct proportion to the degree to which its external opposition relents or is overborne. A corollary follows naturally therefrom: In the event that the left’s external opposition completely relents or is completely overborne, totalitarianism will always result. And in such an eventuality, the final corollary is that Once totalitarianism has been established, the only external checks come from the laws of reality and economics themselves. This too we see borne out by history: The Soviet Union collapsed entirely. The Chinese communists bowed to the laws of economics and began allowing some free enterprise. The North Koreans have begun doing the same. All had no domestic opposition, but had to yield to the facts of nature.

Questions, thoughts, complaints? Feel free to contact me at chriscook@theadvocates.org.