On paper, everyone in the freedom movement prefers some measure of decentralization. Anarchists want more than non-anarchist libertarians, and libertarians want more than conservatives, but we all want some—from federalism, subsidiarity, localism, and minarchism all the way to voluntaryism and devolution down to the individual level.

On paper.

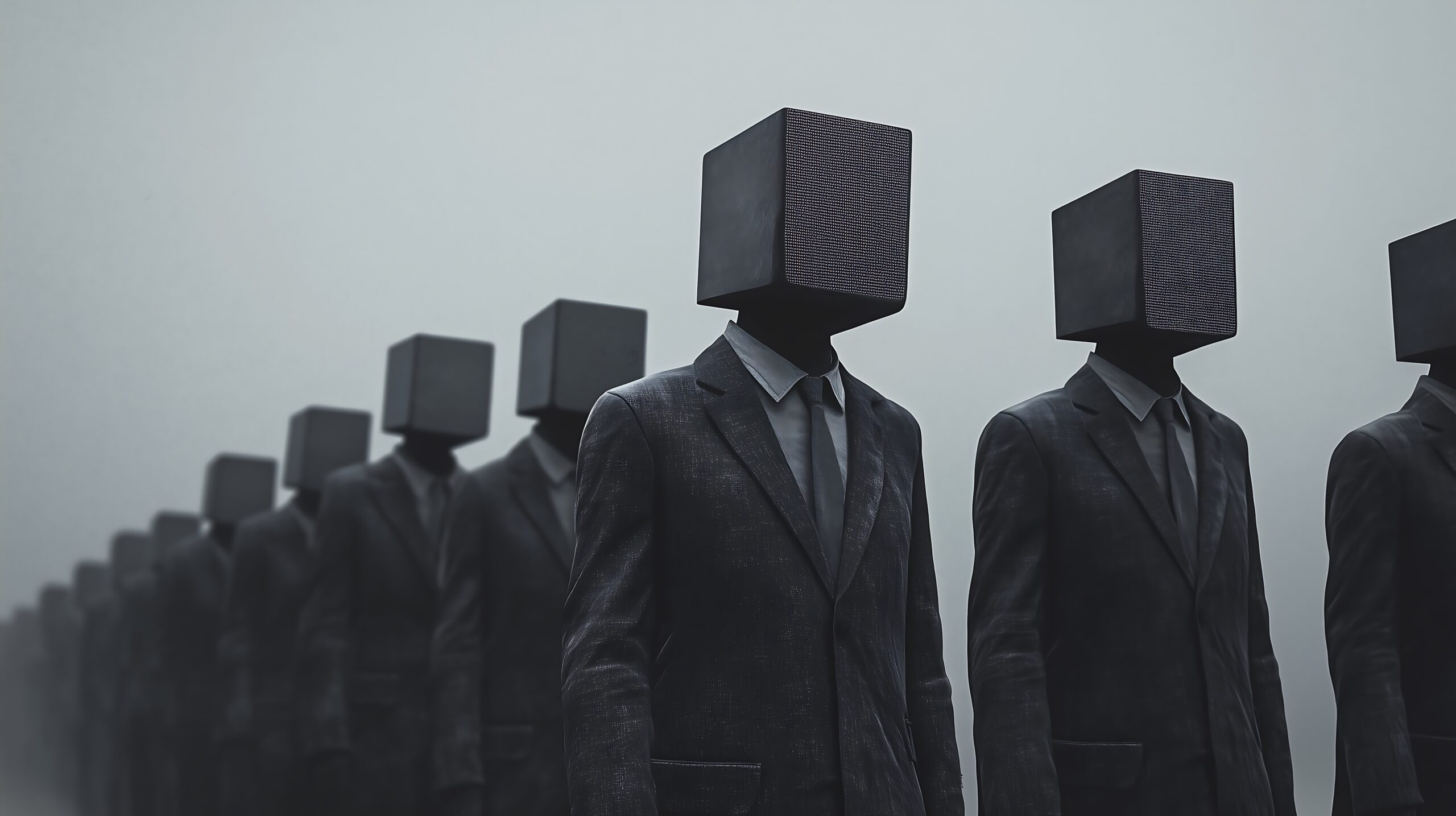

In practice, we are flawed humans, subject to many of the same foibles, misconceptions, and temptations as anyone else. We want others to see things as we do. We worry that unless everyone is singing from the same page of the same hymnal, we won’t be able to make any progress.

We even have our own variant of the left’s “totalitarian temptation.” Theirs destroys nations and lives; ours merely reduces our effectiveness as advocates for freedom. Nonetheless, this is one of the things we must face head-on if we want to help our species evolve out of the statist cycle in which we’ve been trapped for the last few millennia.

Movements and activists often chase unanimity of thought and action. For the freedom movement, however, these are neither desirable nor possible nor necessary.

#1

Unanimity of thought is neither possible nor desirable nor necessary.

It is not a matter of opinion but of fact: no two people will ever agree on absolutely everything.

There will always be disagreements. Even when two people generally agree upon a topic, there will always be nuances of disagreement on the details.

How boring would the world be if it were not thus? How tyrannical would it be if God (for those who believe) had created creatures who agreed about everything. Would we even be free?

Free will and individualism are central to most moral justifications for libertarian principles. We should be the last ones seeking unanimity of thought. And yet, in a weird way, we frequently do.

This is where our little totalitarian temptation comes in.

For libertarians and anarchists especially, first principles are very important. We’re trying to discover and understand them. Most of all, we’re trying to get them right. After all, they’re first principles: exactly the sort of thing that one feels compelled to get right.

Then, we add in the external pressures. Freedom is under assault at all times, from nearly all sides. Control freaks are eager to control. The compliant are eager to comply. Beneficiaries of the welfare-warfare state want to keep the gravy train rolling. As such, we feel compelled to find some magic-bullet response—an ironclad case that what they are doing to us is impermissible.

And so we seek perfection. Perfect arguments. The perfect wording for perfect principles.

To a degree, this is a positive pursuit. But it has a tendency to become toxic as soon as one thinker’s pursuit of perfection butts up against another’s:

You spend months or years seeking a perfect understanding of first principles, or crafting the perfect plan, only to discover that someone else’s process led them to a different wording, a different plan, or a different view on one of a long menu of sub-issues. But how can this be, when your process had led you to perfection?

Next thing you know, we’ve got sea otters bickering over whose “answer to the great question shall prevail.” If you’ve been in the movement for any amount of time, chances are you’ve seen it yourself. (Not the sea otters part.)

The real totalitarian temptation—of Mao, Pol Pot, et al—leads to failure, destruction, and population-scale murder. Ours just leads to endless debate over doctrinaire details. But the debate can be paralyzing.

It is not possible to get everyone to agree on everything. It is illogical and dangerous to keep trying to achieve something that is factually impossible.

Even if some sort of ideological monism were possible, we would not want it. Russian composer Alexander Scriabin (1871–1915) was fascinated by the occult, and toward the end of his life, he became obsessed with finding a chord that "captures the totality of divine powers.” Scriabin used this “mystic chord” to create fascinating and deeply atmospheric music, but you wouldn’t want it to be the only thing you ever listened to again.

There isn’t just one chord, one tonality, or one style of music, and that is a very good thing. The same applies to ideas in the quest for human freedom: variety is a good thing. Pluralism of thought produces more thoughts. More questions. More answers.

More is better. Each of us is painting some portion of a much larger canvas, and together, the picture is far more complete.

Finally, unanimity of thought simply isn’t necessary. Yes, we have to be in the same ballpark. But we do not need to pursue perfect ideological unity in order to make progress. There is so much we can do when we stop worrying about the finer details and just roll up our sleeves together.

#2

Unanimity of action is neither possible nor desirable nor necessary.

Together, however, does not have to mean everyone all at once.

Another variant of our petty-totalitarian temptation is the pervasive belief that a movement cannot succeed unless everyone—or at least a large number—is a part of it. This can lead to aggressive pursuit of agreement and, ultimately, the kind of splitterism we discussed in parts 1, 2, and 3.

I recently encountered a textbook example of the desperation that so many feel to get their particular viewpoint adopted by others.

On the surface, it was just another variant of the minarchism vs. anarchism debate. Unfortunately, the viewpoint of these particular minarchists was more than just the boilerplate, Hey, I think some government will work better than none at all. No, they were far more specific: Not only must there be some government, but it must be exactly this kind and no other. And anyone who doesn’t agree is a blinkered moron.

My response, and that of others, began as respectful and measured. Hey, we’ll check out your ideas. But that wasn’t good enough: Check them out now, or you’re a coward. Our reply—that there may be more than one reasonable pathway to victory—fell on deaf ears, and it just got uglier from there. It felt like we were talking with cult members.

Granted, this was a somewhat extreme example. Most of these things just result in debate and disagreement, and possibly some scorn and disinclination to work together in future. This one was extra ugly. But it is exemplar for two reasons.

First, these folks really were (I am somewhat sad to say) in the freedom movement. They believe in the same core principles and share the vast majority of the same ultimate objectives as the rest of us (as I kept making clear, in my effort to keep the peace). Sadly, their answer to the Great Question was the only possible answer, and that was that.

Second, I could tell that they were motivated by the fear that without widespread adoption, their ideas will die on the vine. That was instructive.

It is a concern that repeats itself again and again in movements such as ours:

Eureka, I have figured it out! I have discovered the perfect answer. I have devised the best way to proceed. But how will it go anywhere if no one joins me?

We have many smart people earnestly toiling away in sincere efforts to find a way to make human beings more free. Yet their great ideas frequently wither for want of widespread acceptance. It is a frustrating and lonely feeling.

It is absolutely true that there is strength in numbers. The more people who adopt, proclaim, and act upon a given set of ideas, the more likely it is for those ideas to gain broader traction.

Yet we must remember a few things.

First,

It is impossible to get everyone to join in on any endeavor. No matter how hard you try, you’re not going to get everyone to follow you, join your group, or adopt your approach. Even if it’s really, really good. Even if you are the most charismatic person in the history of charismatic people.

One way to deal with the problem of splitterism is to accept this fact and not get too angry about it.

Do your best. Try to convince people. Nothing succeeds like success!

But you can only do what you can do. If you can dial back the frustration at the fact that not everyone is going to sign on to your plan, or to your particular interpretation of first principles, it will reduce the resentment that leads to rancor and separation.

Second,

The other side of that coin is to embrace pluralism rather than resenting it.

We should be cautious about falling prey to the 'one true way' fallacy, as Max Borders has called it. The fact that we are laying many different pathways to the promised land is not a flaw; it’s a feature. Competition, experimentation, and polycentric efforts are far more in keeping with our core principles and values. Embracing a decentralized approach makes us more of who we are. More of what we’re meant to be.

Imagine if everyone joined on board one particular effort. What would that look like? All our diversity of thought, all the advantages of applying pressure from many different points, would all be washed away. Might we be more effective for a time? Probably. But at what cost? American Republicans have a big tent, and all they do is propose a lite version of their opponents' program. They are effective at perpetuating the system—and little else.

A bit more organization and a renewed focus on practical solutions would definitely benefit us. But we do not want anything even close to unanimity or a centralized approach. Ultimately, the world we want is polycentric. We are not going to get to that world by being monocentric.

Be a leader. Don’t try to be the leader.

Tell people how awesome your ideas are. Be loud and proud. But do it in a joyous way—one that openly acknowledges that your way may not be the only way.